There's more to car culture than racing, but it's undeniable that the moment the automobile was invented, people were already wondering, Hey, how fast can this go? Japanese Americans have explored the dimension of speed for over 110 years, from the Mojave Desert dry lakes to urban drag strips to late night street races. Meanwhile, intrepid mechanics and engineers have innovated ways to boost performance on everything from Indy cars to everyday imports. Wise racers will warn you, never underestimate the Nikkei who pulls up alongside you in an unassuming car because you never know what's under the hood.

過去の展覧会

Cruising J-Town

Audio Tour

Seven years in the making, Cruising J-Town is one of the first exhibitions to ever highlight the rich history of the Japanese American community here in Los Angeles, and its long relationship to the world of cars and trucks. The stories cover everything from import tuners to gardening trucks, auto designers to gas station mechanics, prewar hot rodders to 21st century drift racers.

At the heart of Cruising J-Town are the personal and family stories of the Nikkei community and how they shaped car culture—and were shaped by it—over the past 110 years in Southern California.

Please enjoy this audio guide, organized by themes that correspond to the exhibition sections. They include in-depth, bonus content to enrich your experience while visiting the exhibition, on view through November 12, 2025, or to explore at any time from wherever you are.

Scan the QR codes in the exhibition or click on the menu below to take the audio tour.

View photographs and take the audio tour through the free Bloomberg Connects app. LEARN MORE

Audio Tour

2025年07月31日-12月14日

Peter and Merle Mullin Gallery

ArtCenter College of Design

1111 South Arroyo Parkway

Pasadena, CA 91105

Audio Tour

Seven years in the making, Cruising J-Town is one of the first exhibitions to ever highlight the rich history of the Japanese American community here in Los Angeles, and its long relationship to the world of cars and trucks. The stories cover everything from import tuners to gardening trucks, auto designers to gas station mechanics, prewar hot rodders to 21st century drift racers.

At the heart of Cruising J-Town are the personal and family stories of the Nikkei community and how they shaped car culture—and were shaped by it—over the past 110 years in Southern California.

Please enjoy this audio guide, organized by themes that correspond to the exhibition sections. They include in-depth, bonus content to enrich your experience while visiting the exhibition, on view through November 12, 2025, or to explore at any time from wherever you are.

Scan the QR codes in the exhibition or click on the menu below to take the audio tour.

View photographs and take the audio tour through the free Bloomberg Connects app. LEARN MORE

Audio Tour

2025年07月31日-12月14日

Peter and Merle Mullin Gallery

ArtCenter College of Design

1111 South Arroyo Parkway

Pasadena, CA 91105

Audio Tour

Seven years in the making, Cruising J-Town is one of the first exhibitions to ever highlight the rich history of the Japanese American community here in Los Angeles, and its long relationship to the world of cars and trucks. The stories cover everything from import tuners to gardening trucks, auto designers to gas station mechanics, prewar hot rodders to 21st century drift racers.

At the heart of Cruising J-Town are the personal and family stories of the Nikkei community and how they shaped car culture—and were shaped by it—over the past 110 years in Southern California.

Please enjoy this audio guide, organized by themes that correspond to the exhibition sections. They include in-depth, bonus content to enrich your experience while visiting the exhibition, on view through November 12, 2025, or to explore at any time from wherever you are.

Scan the QR codes in the exhibition or click on the menu below to take the audio tour.

View photographs and take the audio tour through the free Bloomberg Connects app. LEARN MORE

SPEED

Introduction

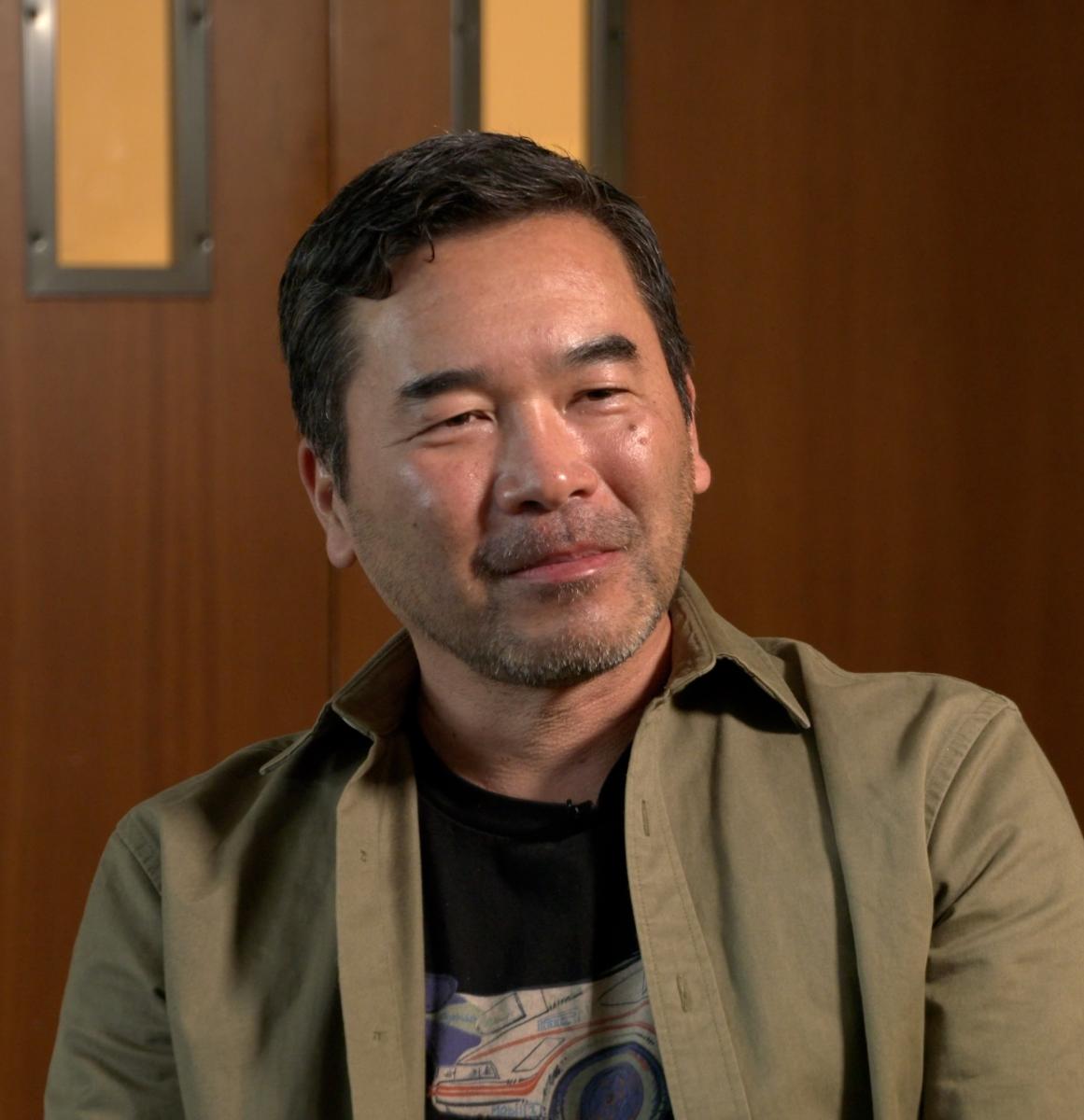

Curator Oliver Wang introduces the “Speed” theme

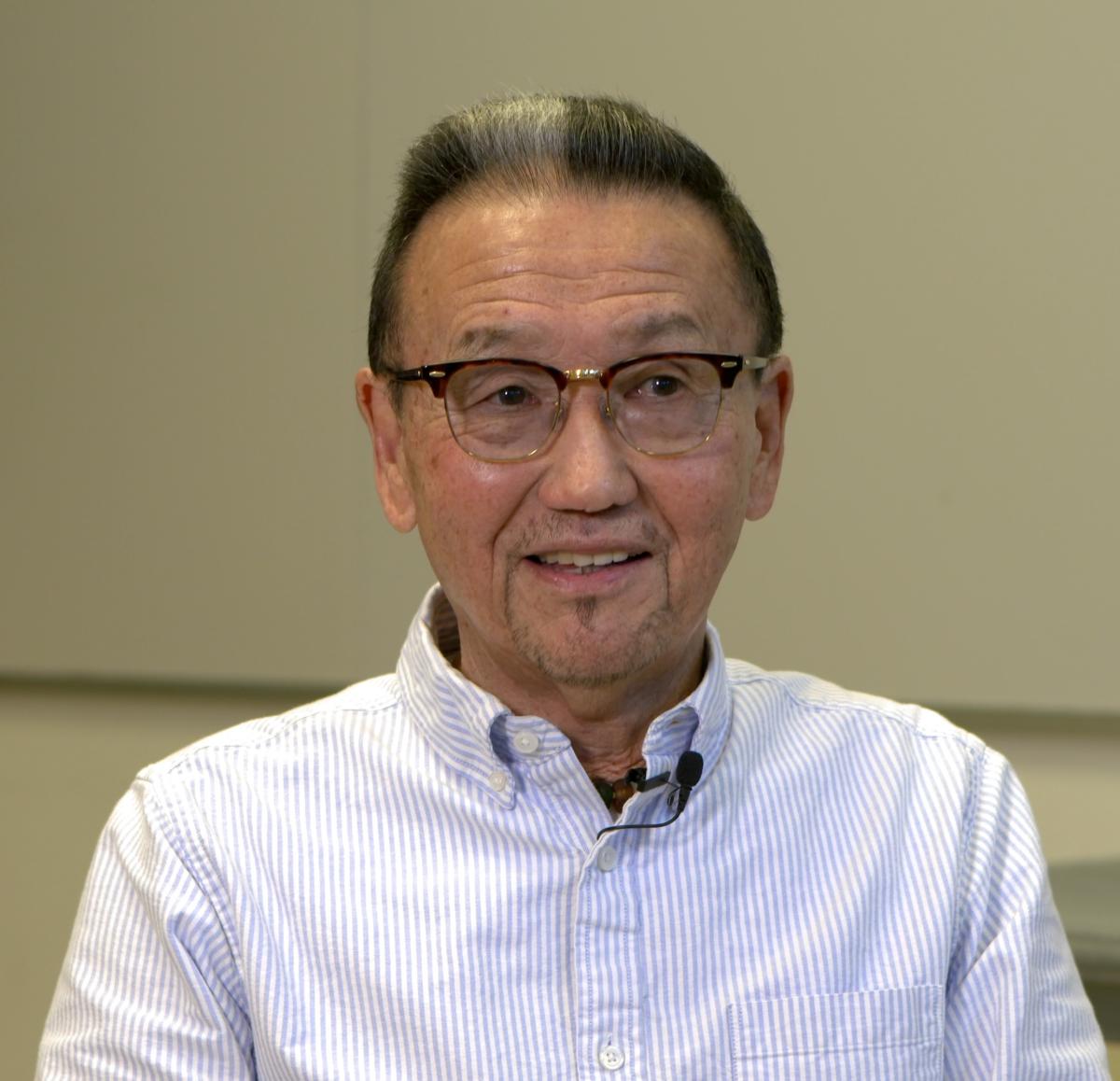

Tod Kaneko

Tod dives into his passion for customizing his Datsun 510.

Tod: Okay. My name is Tod Kaneko. I'm Nisei here, second generation Japanese American. I would say I grew up in the South Bay, primarily the Torrance area. Actually, my grandfather came, so he was the first Issei here. And my dad. And I'm actually a Sansei.

Oliver: All right, so your grandfather had that interest. How about your other relatives, your father?

Tod: Yeah, so again, my dad had a whole bunch of cars when he grew up too. So, his favorite was the T-Bird back in the day, and a GTO, I could really vaguely remember that. But he was, again, very mechanically inclined, so I kind of picked it up from him, as far as the car interest.

When I started getting into the cars, I started off at the Capri, actually. That was my first car, and I actually bought it from my friend that kinda introduced me to the car scene. Back then, he took me to my first Nisei Week, right?

Oliver: Okay.

Tod: So, we were cruising there, and he actually raced on First Street in front of everybody. So, that just really caught my attention, and kind of the love for the car culture. So, that's my first, I guess, experience, and it kind of led me down the path for enjoying cars.

So, that goes back again, I was fourteen, I couldn't drive, so I was a passenger with my sister's elder friends. So, my first Nisei Week, again, can I name names? So, my buddy Glenn Quatta had a Capri, a very, very fast Capri. So, he took me out on my first Nisei Week cruise, and I was just astounded by how many people were there. And after the event ended, how many people just lined the streets to watch the cruise. And I thought, "Wow, this is really astounding."

And just by chance that evening, he actually raced on First Street in front of everybody. So, again, being a young kid, I thought, "Wow, this is great." Right?

Oliver: Right.

Tod: So, that really kind of locked me into this whole subculture of cars and the cultural scene.

Oliver: So, when's the first time you were able to drive yourself, and was it with the Capri, is that what you took out there?

Tod: All right. When I was legally of age to drive, I actually drove the Capri. I actually bought the Capri from Glenn. So, that was my first car that I learned to wrench on. Learned a lot of good things, made a lot of mistakes, but that was my first toy. So, again, after that, I got the job with Joe Hunt, and I really got the professional viewpoint or knowledge from them, and really just I think it elevated me from just the knowledge and be able to produce really fast cars and engines. Some of the guys that Joe grew up with.

There was a guy named Ed Iskenderian, who's real famous for Cams. Another guy named John Shaver who built really, really fast race engines. So, those guys actually helped me get my knowledge, based on how to build cars or build engines. But, yeah, so it was that Capri in Nisei Week that kind of set my destiny, in a sense.

I think I always wanted a 510 as my first car, but I couldn't afford one, so that's why I had the Pinto. But again, I think the association to an import brand was also gaining momentum back then. Parts were becoming more available, so the whole tuning aspect was becoming a little bit easier. And back then, everybody tuned in the garage, so everybody actually wrenched and did their own work. We worked on cars back then. But the domestic side, I mean, it had its own culture, but I think the import side was something new and fresh. So, I think that's why a lot of people, at least the Japanese Americans, trended toward the import cars. And again, kind of reflects back on the heritage as well.

So, again, I think from my perspective too, why I went toward the import cars, were obviously they were smaller, lighter, smaller engines, but you can actually make these smaller engines in lighter cars faster than the domestics. So, back when I used to race, I mean, there were some racetracks out here like Terminal Island or Orange County Raceway, I'd line up against big block Camaros or Chevelles, and still beat them. So, again, kind of shocked a lot of these domestic people. You know, little, small rice burners, as they may call it, can just outdo the bigger muscle cars.

Oliver: You also mentioned that there was kind of a pride to it. And so I am curious, because I mean these are car companies coming from Japan, and even if a lot of the people that were getting interested in these cars were themselves, you know, Sanseis, like, I mean, they were three generations removed from Japan. Did you feel like there was some kind of ethnic pride that was associated with driving a Japanese car when you are of Japanese descent?

Tod: I think so. I mean, again, it makes me closer to the community that I'm part of. And again, I think that the technology was also a little bit more advanced than the domestics at the time. So, that's something I always wanted to leverage. And again, I'm always for the small guy beating the big guy. So, the small engine beating the big V8 engine was very, very nice at times.

Oliver: What are some of the examples of the kind of technological advances that you saw coming in on these Japanese imports, that were not in the American domestic scene then?

Tod: So, back then, it's kind of funny. So, back to the Pinto. So, my first Pinto engine was a turbocharged two liter, four cylinder, and they made about 450 horsepower, which was probably equivalent to a good V8 back then. But the key items back then was turbocharging. So, you're actually force feeding the engine, your air and fuel to make the power. So, again, technology kind of drove me to these little bit smaller engines.

The next engine I did was a rotary engine, which is very unique as well. And those things, easy a two rotary 13B, they're making 13, 1400 horsepower right now in the drag scene. So, they're more than capable to keep up with the domestic V8 products.

Oliver: Were these equally easy to work on?

Tod: If you have the right knowledge and background, it certainly is. There's no magic behind that.

Oliver: You have been also part of the, for lack of maybe a better term, the classic Japanese car scene. Obviously, you think about things like JCCS, the growth and interest around, I mean, the car that's right in back of you, for example.

So, what was it about cars, specifically, like the 510s and the Zs that at least were appealing then, or at the very least are appealing now for collectors who are interested? What was it about these specific models that really drew people's interest and attention?

Tod: Well, let's see. So, the Z and the 510 was my initial love. Again, I couldn't afford it when I was young, but today I still have a Datsun 510 and a Datsun 240Z.

But I think a couple of things behind that. I mean, again, it ties back to the Japanese culture. These came from Japan, we're Japanese American. But also to the potential the cars have to make them fast, and the potential to beat the bigger domestic V8s was also key.

Also to Nissan, especially Nissan, well, Honda, Toyota as well, but they have a big heritage of racing history in Japan. So, they were basically already proven cars when they got here. So, we knew their capability. So, again, that was another drawing interest for me.

But again, I think when they brought the 510 over, the Z over, same thing, they were beating all the European cars and the domestic cars. So, that's one reason I fell in love with these cars.

Oliver: Right. It had to do with their success on the racing scene, is because if I recall—

Tod: Well they raced in different scenes, but the biggest one for North America was the Trans Am Series back in the day with Pete Brock and John Morgan.

Oliver: So, yeah, explain the importance of Brock and what did he do for the 510?

Tod: Well, Pete has a big design background history with the Shelbys, et cetera. But he also ran the Nissan factory program for the Datsun 510 and 240Z. But again, I think he put the 510 and the 240Z, he raised that, elevated that awareness greatly. And even today, I think you're still leveraging that past BRE, which was Brock Racing Enterprise. Right?

Oliver: Right.

Tod: So, again, that history never died, and I think it's still growing. Yeah, well-

Oliver: You actually had these cars back then?

Tod: Well, yeah, I mean I finally got my 510, right?

Oliver: Yeah.

Tod: And then got the Z. So, really, I'm not shopping for anything right now.

Oliver: Tell me the story behind this car. When did you get this?

Tod Kaneko: So, I got this... So, my first car, first import, would've been the 510. This car is a funny story. So, I was building the 510 at home at my parents' house. My buddy owned this car, and he bought it brand new, and he started to work on it at his mom's house. Pulled the engine out, and then it sat for, I don't know, fifteen, twenty years. And his mom said, "Get rid of this thing."

So, he asked me, "Hey, you want to?" I mean, I got a super killer deal on it. It didn't have an engine, but it was perfect shape, and everything. And I didn't need a second car to work on, but I couldn't pass up the deal.

Oliver: So, what year did you get this, roughly?

Tod: Probably mid-eighties.

Oliver: Okay, so you've had this for forty years?

Tod: Oh, yeah, yeah.

Oliver: Okay. Yeah. The way that you made it sound, you sounded like, "Well, I got the Z", but it made it sound like you got it like the last three years.

Tod: Oh, yeah, yeah, no.

Oliver: So, you've had it—

Tod: Yeah, I had another project, the 510 going on. I'm thinking, "I don't need another project", but I couldn't pass it up. Yeah.

Oliver: You've never been tempted to sell it? I'm sure you've gotten offers.

Tod: I've got offers, but yeah, I haven't finished it in a sense. But yeah, it's never ending, right?

Oliver: Yeah. What does finishing it even mean?

Tod: There's little things I still want to do. The pet peeve stuff, tuning stuff, and latest technology stuff I want to put into it. It's kind of a toy for me.

Oliver: Have you customized much of the exterior?

Tod: Basic shape is still factory stock. Yeah, I didn't go crazy with the big flares, or big wings, or anything like that.

Oliver: Yeah. And how about the interior?

Tod: Interior is basically pretty much stock too. Yeah.

Oliver: I'm assuming the engine probably not so much.

Tod: Not so much. That's my toy land, I like to tinker with.

Oliver: Right. And you said you bought it without an engine anyway, so you had to basically construct, build an engine or it?

Tod: Right.

Oliver: And so the 510, you've also had since the eighties?

Tod: That's true too.

Oliver: Right. And that's the one that has a rotary engine.

Tod: So, yeah, turbocharged rotary, yeah.

Oliver: Would you ever consider selling that?

Tod: Probably not. Again, it is still a work in process. I mean, we're trying to get it ready for a track event. So, it's kind of funny. My nephew, I think you interviewed already, Billy, right?

Oliver: Yeah.

Tod: Billy Johnson. So, when he was young, he's probably sixteen maybe back then, I had the 510, had the rotary, and we're at the track up at Buttonwillow. So, I said, "Hey Billy, you want to drive us in this time attack event?" So, he jumped in, and he was already a very talented driver back then.

Oliver: Even though he wasn't old enough to have a license yet?

Tod: Yeah, I think he was sixteen. But he just finished that Formula BMW series. Right?

Oliver: Right.

Tod: He won a scholarship to that. So, he's back in the States. So, he jumps in and he just tears it up and just dusts everybody. Right?

Oliver: Yeah.

Tod: And again, that 510's a really old car. We were racing against the Subarus and the Evos, and half these people didn't even know what kind car that was. They're coming, "Hey, what kind of car is this?" "It's an old '72 Datsun 510." But with his talent and that car, the way it's set up, it turned a lot of heads. It was pretty funny.

So, right now we're trying to resurrect it. So, it's been, I don't know, twenty-something years since we did it. And I told Billy I'll get the car back together, we'll go out with the same crew, and go have fun at the next Time Attack event. So, that's work in process.

Oliver: : Yeah. So, that's why it's in the shop right now?

Tod: Yeah, we're working on it.

Moto Miwa

Moto tells the story of how he built his Toyota Corolla AE86 forum, Club4AG.

Moto: My name is Motohide Miwa, uh, Moto. I live in Torrance, Gardena area, but I'm originally from Japan. Migrated in 1978.

Oliver: And what generation Japanese American are you?

Moto: Should I say 1.5? What do you call somebody who came with their parents?

Oliver: Yeah, 1.5. You'd be kind of like a different kind of Shin Issei, I suppose. And I should've asked, do you identify as being Japanese American?

Moto: Yes, because most of my life, I've been here since nine years old in California, grew up in San Francisco Bay Area and I've been in southern California since '92. That's when I ran into my Corolla project is I was hanging out at one of the shops, one called Toy Sport in Gardena. It's operated by a couple of Filipino brothers who used to be very close with Toyota because they were the son of a taxi fleet company in Manila who took on Toyota Crowns as their fleet cars. So they basically opened up Toyota's market in the Philippines, and their sons were here working with Toyota, and they had a little shop and they had this Corolla sitting that was just kind of stripped to the bones. And they just kind of ran out of funds and they weren't doing anything with it, and they offered me, "Do you want to build this? I'll sell you this for $500, and you can just put all the parts and you can just buy all the parts to put on. You can make it any way you want it."

Oliver: So basically they sold you a shell?

Moto: Shell, yeah.

Oliver: And what kind of Corolla was it?

Moto: It was an AE86. And it was something I wanted to buy when I was sixteen that I couldn't, because at the time it was $11,000 when the Civic was $8,600. I had no experience building a car from scratch, but I hung around with them enough that that could be done. And I had another car at the time, so it could be interesting watching this long-term project evolve. So that was my thing and then a few months later, this Corolla just... I drove it out of there, nice fresh paint. I mean, it looked very nice. And then they said, "Well, let's take it autocrossing."

So I started on this journey of autocrossing this car and met a bunch of friends there. This is mid-nineties by then, I think. But yeah, through building the car, I met a lot of other people that built cars, R.J. de Vera and Don Fujita, and all of those people that were just winning car shows left and right. They had the tallest trophies at any car show they went to. And Ken Miyoshi's Showoff series. So I was kind of friends with them all in the Southern California, Gardena, Torrance area that we were just very close by then. Just getting together.

There were already forums, you know, car forums which my start in having this much reach too is originally in the late nineties, I think it was ’97. This whole World Wide Web thing was becoming more of a future of things. And I knew eventually I would need a website for my restaurant. I said, "This is going to look like crap if I just make a website now. I don't know how to do it and I don't have a budget to hire anybody. So what I'm going to do is I'm going to practice. I have all these notes and random pictures of my Corolla being built. So I'm just going to put that up and then I'll just add to it as things go."

And then pretty soon there's hordes of emails coming in. "What are you doing about this?" "I'm doing this in Australia, but I'm stuck because I don't know which transmissions..." That sort of stuff. Because all of this information in my head was in Japanese, in Japanese magazines. So slowly I would translate these to English. And then suddenly, just in very short period of time, this website called Club4AG that I put up as a practice thing for my restaurant, turned into a center of English information regarding AE86 Corollas. So I put up a forum, and that became pretty much a benchmark standard of where to find information on Corolla by everybody's account.

There's a lot of people globally that knew a lot about these engines or had a lot of experience. And then there were others who were racing it actively that were just kind of blogging their progress, so everything that had to do with that AE86 Corolla in the English language was posted there. There was also a place where they can put reference information or history or whatever. I mean, there's lots of things that were archived there.

It just kind of expanded it to a lot of different Toyota cars and then stuff that's general like driving skills topics or racing topics would apply to any car. So it was a big healthy community and it kind of scattered into different places and offshoots. And I think early 2000s was right in the era when everybody was on a forum somewhere. That was the social media of its day. So even if they weren't on Club4AG, I could post something on another guy's forum and if it was interesting, then it would reciprocate and just go everywhere. So yeah, that's how we got 12,000 people to come into Irwindale Speedway, where NASCAR was never able to fill that venue ever. And that's when it, I think, hit a lot of the racing industry people because racing was a dying thing in Southern California as far as venues.

John and Dan Kuramoto

John and Dan talk about John’s racing journey from quarter midgets to go-carts.

John: My name is John Kuramoto. I was the youngest of three boys. My middle brother, Daniel, is right here (Dan laughs). This is Dan. We have another brother, Ford, who is six years older than I am.

Dan: We were born and raised in Boyle Heights and he's still there.

John: Born and raised, Los Angeles.

Oliver: And what generation Japanese American are both of you?

John: Sanseis.

Oliver: Sanseis.

John: And I don't remember having any particular idea in my mind, necessarily, other than I like cars because we saw them a lot because of my father.

Oliver: Sure.

John: Then one day we get under the car, Dad says, "I want to take the whole family. We're going to go out near Disneyland." And I don't remember if ... And we get to Ball Road at Disneyland, and we pull off and it's right off the, what is that, 5 freeway? And soon as we pull over, we hear all this noise, this rhaeeeh rhaeeeh raheeeh. And we walk out there, and we all walk out there, and they're racing. And there was a pretty good group of them. And they're racing around the track. And the smell and the noise captured me like I was pinned. And I watched these kids race. And I look at them and I say to myself, "This is just unbelievable." This is quarter midgets. And we went to go see our parents' friend, the Shojis. The Shojis had been racing in quarter midgets for several years.

Dan: They were from Upland.

John: And they were from Upland. They're at that time, as far as we knew, the only Asian family, Asian driver, Asian car out there that was racing quarter midgets. And so we met the family, we met Carl. Carl Shoji, was I think believe a chicken farmer in Upland. And he introduces us to his son, Richard. Richard was a champion racer at that time. And I remember we stayed there and watched the race. And I don't know, I was just like, in my own world, I just couldn't imagine what I was seeing, and I was loving it so much. And I don't know why, because I had no indication that I should be a race car driver or have any place near these vehicles. I was chubby. I wasn't athletic. I never indicated this is what I wanted to do. But when I saw it, it hit me.

John: And then I remember when we stayed and watched the races, and Carl Shoji came up to my dad, towards the end there. He goes, "Jack, you should get one of these. You should race one of these. You've got the shop, you know you would be so good at this." And he said, "You'll be so good at it. You have the service station." And then he looks down and I'm standing there. "And have him drive, he can drive." Okay.

Dan: And functionally the engine was basically a lawnmower engine, which is a kind of interesting spin and irony about JAs and that generation of gardeners like our grandfather. And then here was my dad working on a lawnmower engine, and my brother, the first time he got in it and drove laps, people said, "He's a natural." I mean literally. And he won his first race.

Oliver: So basically go-karts were in a way kind of an offshoot of the midget scene because you had the same people working on it. And-

John: The big difference, though, is age, right? Don't forget, quarter midgets is for kids.

Oliver: Yeah.

John: So go-karts immediately are for adults. They did have kid categories. After I stopped racing quarter midgets, I was asked by the same go-kart company, Duffy Levinson, who's a great friend of Jimmy Imani, they offered for me to be a team driver and they had everything there. "Here's a kart, here's this, here's engines, here's this." He goes, "What we'd really like you to do, we know you can drive. We'd like you to go out there and set track records. Can you just go out there, give it a good effort? That's all we are." I go, "I'm down." The reason we got involved, because Richard Shoji had switched over. He was sponsored by a company, the second-largest company called Bug Go-Karts. And he was already switched over. And he was doing well. He was doing well and going fast. So then they heard, well, there was another guy, Richard's friend.

Oliver: Right.

John: And that's when I got—

Dan: But at this point he had already won three national open field championships in quarter midgets, which at that point was sort of at its peak. And then his picture was on the cover of Hot Rod Magazine, and Car and Driver, and all this stuff. And so he was kind of aligned perfectly to make that next move and into go-karts. And my family benefited from it because they gave him every kind of conceivable thing that they made.

Oliver: Right.

John: We raced, I think almost four years, quarter midgets. I probably did two with go-karts, right?

Oliver: Yeah.

John: Because I was getting to be, I wanted to be sixteen so bad. I wanted my own car. What a guy like me, after you're racing, you're like, "God, I just want my own car. I want a real vehicle."

Oliver: Right.

John: And—

Dan: To me, the highlight of a nice car was that you might get to take out the girl that you wanted to see because you had a ’57 Chevy, which my dad gave me, that was completely the most cherry—

John: Was—

Dan: ... perfect—

John: Custom.

Dan: ... multi, candy apple blue with custom rims and everything until I totaled it.

John: Uh-oh.

Dan: Yeah.

John: Then I remember my oldest brother taking Dan and I outside, and giving us a talk. And this was after we just won the quarter midget, and he started telling me about family values, and about how he is willing, in the circumstance we have now, that we won the quarter midget, it looks like we're going to start racing.

Oliver: Okay.

John: And everyone has to make a commitment as a family. We are our Nikkei racing family. And what does that mean? And I listened to him. And the fact that he ... Maybe I didn't understand the words so much, but the fact that he supported what we were going to do, then he passed it to Dan and said, "Dan, we're going to need to do this. We're going to need to support John." And Dan said, "Okay." And I'm thinking, "For these guys to support me and ready to go, and I haven't even raced my first race. I haven't proved nothing yet. All we proved is we won the quarter midget."

Oliver: Right.

John: So I'm thinking, "You know what? I want to do well because of my family." We were a close family. It was a close racing family.

Scott Kanemura

Scott talks about his journey from BMX racing to street racing for money.

Scott: My name is Scott Kanemura. I was born in Inglewood, but raised in Gardena.

Oliver: What generation of Japanese American are you?

Scott: I'm Yonsei. Fourth generation.

Oliver: Did you have any family members in the camps during World War II

Scott: No, Unfortunately my parents, they grew up in Hawaii, so they didn't have camp out there.

Oliver: Very good. Since we're going to talk about cars, what cars do you currently own, and what significant cars have you owned in the past?

Scott: Well, I have this Toyota 4Runner in the background that I'm planning to take to the SEMA show, to compete against in the Battle of the Builder contest. I also have this really bright Scion XP, that was a former SEMA car from 2014. My past cars, I had... my first street racing car was a 1974 Toyota Corolla, and it was a fully built motor with nitrous. I also had a 1987 Honda Prelude, and a 1990 Acura Integra that used to... I used to shoe race, the Integra. The Prelude, we just put really loud stereo system in it. Back then, it wasn't really cool to do Hondas too much. Everybody used to tease me about driving a college girl car. And then I think afterwards, it started catching on to be a cool car to modify.

Oliver: Why were Hondas not as popular back then?

Scott: It was more like college girls would drive the Honda.

Oliver: It was just that stigma.

Oliver: Were there other car brands that have this similar views? Or not views, but stereotypes?

Scott: I guess the import culture. It was a lot of Datsuns and Toyotas and Mazdas. And even American cars were really known in that culture. Like the Ford Pinto and the Mercury Capri were very popular. It was more not where the car was manufactured, but more the style of what the import culture did.

And his name is James Sugimoto. Unfortunately he passed away way too early. Cancer sucks. He always wanted to include people. And I owe him why I started getting into cars. So, basically, I was racing BMX bikes until six months after everybody else started driving cars. And one night he was like, "Hey man, forget that BMX stuff, man. Let's..." he gave me a ride in his brother's fixed up car. And he decides to do burnouts and stuff. And he lived across the street from Ellen Junior High School. So we're doing burnouts and we're having fun and everything. And all of a sudden a cop comes. And he starts chasing us. And then we were going around and we were going all through the neighborhood and stuff. And then we got away from him. And we pull over on the side of the road and then we duck. And then we're like, "Ah, we got away."

And then all of a sudden, the cop comes and starts pounding on the window, like, "You dummy," very clean version. "You dummies. You know why we caught you?" And we were like, "What?" And he goes, "You had your foot on the brake." So the brake lights were on. So that's how he caught us. And then I was right near my friend Jim's house and his brother and a girl were hanging out there. And she sees the cop pull us over. And she comes running up. And she has a really short mini skirt on and a low cut. And then she's pleading to the policeman, "Don't arrest my little brothers. Don't arrest my little brothers." And then allegedly, somebody called the police and said, "Somebody's breaking into the junior high school. So you guys got to get down there right now."

So the police got down on the radio and they said, "You're lucky we're letting you go. We have to go the junior high." And then they took off off. So we had running away from the police. We had girls in short mini skirts and low cut tops, and we got away with it. So I was hooked on cars after that.

Yeah. Our group, the KMA group, I think almost 90% of them started in BMX, and then they progressed onto cars after. So it's definitely... that's how we knew each other from riding the dirt tracks in our neighborhood and stuff like that. So it was definitely a big influence on everybody.

Oliver: So the neighborhood you grew up in, what was the car scene like in the 1980s? What really stands out to you about that specific era?

Scott: There was a lot of Datsun, so I know a lot of people have that BRE influences and stuff. In in the eighties, there was a lot of Datsun sprinkled with Mazdas and Toyotas back then. Yeah.

Oliver: So does that mean at that point, import cars had already gained a foothold compared to let's say older American muscle, or other non-Japanese brands?

Scott: It had its own niche but I think a lot of the JA guys, they drove American muscle cars as well as... but a lot of them, they got handed down cars from the parents. They had to do what they they had.

Oliver: Which kind of cars were you interested in?

Scott: Believe it or not, I started with an American car. I had a 1966 Chevy Nova. And then I guess I started hearing noise was very important. My friend gave me a ride in his Toyota Corolla and he had these dual carburetors. And that noise and that feeling, and that unique style of the import, the Los Angeles import culture, that pretty much drove me to get rid of the Nova and go to a Toyota.

Oliver: When you say the unique style, can you just elaborate on what you mean by that?

Scott: It was more... I know a lot of people say stance. Everybody would lower the car really low, and put really big tires underneath it, and put a little air dam on there. It just had its own... The import culture has its own unique style. Kind of how the low riders, they say it's more than car culture. It's a lifestyle. I believe in the eighties and I don't know about now, but yeah, we had our own lifestyle. Everybody had the Bruce Lee glasses and Kung Fu shoes, and Members Only jackets and all that stuff. It was more than the car. We had our own thing.

Oliver: That's okay. You're in the middle of saying how it wasn't just about the cars. It was about the lifestyle.

Scott: Yeah. I noticed I talked to a few of the younger guys now. They would say their parents would drag them to Obon festivals and things like that. But when we were growing up, it was really cool to go to the Obon festivals because you would cruise and girls and Okinawa Dangos, and plain dough ball and everything. That was the thing to do all year. Everybody would get ready for [Nisei 00:14:01] week.

Oliver: The folks in KMA, a lot of the other racing clubs, their cars were not 100% Japanese brands. But majority. And how much of that was... most of you guys were JA, so Japanese car brands, there is an identification with it, versus how much of it was because these cars were gas efficient, relatively easy to modify? And frankly, maybe a little bit different than American muscle cars, who just... if you wanted to just stand out. How much of it was tied into the fact that you all were of Japanese descent and why you decided to gravitate towards Japanese imports.

Scott: For me, it was just the look and the style really that really drawn me. And the sound. And growing up in Gardena, I think we had the unique privilege of having a lot of the premier businesses that modified cars. We had Toyota Racing Development right here on Western. And HKS is another big Japanese brand that used to be right here like 10 minutes away. So the parts were pretty accessible for us, especially here in the South Bay.

So I was probably fifteen or sixteen years old, and my friend Jim, the one that I mentioned that got me into cars, he calls me over at high school. He says, "I got something very serious to talk to you about." So I'm like, "What?" So we go and we meet after school, and then he's like, "Hey, do you want to join KMA?" And I'm like, "KMA is a car club. I don't even have my license yet." And then he's like... he went and he made a little Xerox copy sticker, and he goes, "You could be our BMX division." And he made a little sticker just so I could be involved in KMA, so it was just very touching that he wanted to include me.

So that's how I joined KMA, and just continued after I got my car and all the way to the incident where my friend, he ended up getting shot at Pacific Square. And the local newspaper said the gang KMA was involved in a gang fight. So a lot of us had to take the sticker off the car because your parents are like, "Isn't that the sticker you have on the side of the car that says it's a gang?" So we had to back off, but yeah.

Oliver: Yeah. I wanted to make sure we come back to that story. Okay. So first of all, what did KMA stand for?

Scott: KMA stands for Kiss My Ass racing.

Oliver: As far as you know... I know you weren't there, you didn't help found the group, but where did that name come from?

Scott: Just one of the members. I think my friend Jim's older brother, I think he said he decided to just call it that.

Oliver: So what were the main things that you all would do in the club?

Scott: We would hang out at Jim and John's house. We would go to the Obon festivals like OCBC, Nishi, Nisei. That was the thing to do back then. We would go watch movies. Yeah. We would go street racing every week at the Pacific Square, or here in Gardena or... it was called Naugles back then, but now it's still Taco here in Gardena. So we would do a lot of that stuff.

Oliver: Who were the other clubs that you knew that were around at the time?

Scott: There was obviously Shoreline. Shoreline racing was around. Back then, we had a... it started out as rivals. Actually we really hated each other in the beginning. They're called Paradise Creations Racing. And it's really funny how that works out is now we're best of friends what, thirty years later and stuff that. But there was a... our biggest rival who was, believe it or not, it was a more of a city thing. So I don't know if you've watched that movie, The Outsiders back in the eighties. Yeah. So they were the Socs or whatever, and we were the Greasers, because we didn't have as much money as a Torrance guys. So that was our biggest rivals. But nowadays, we're really good friends with them also, so it's kind of cool.

Oliver: And I'm sorry, who were the Torrance... What was the Torrance crew?

Scott: They're just North Torrance. They went to North High.

Oliver: Got it.

Scott: And they're different.

Oliver: And were these all predominantly JA clubs you're talking about?

Scott: Yeah. The majority of them were JAs and from-

Oliver: So what was your first memory of going to a street race?

Scott: Before I got my license, we would go out to the Stadium Way, by Dodgers Stadium. And they would race up the hill. The majority of our stuff in this area, we would race in Compton. And it was more... what's it called? Mans and North... their streets are still there. Anna Maria Street, Santa Fe and Del Amo. So it was just a lot of things.

Believe it or not, I think the thing that actually got it the most accurate is the Fast and Furious movie, believe it or not. In the movie, everybody would just park off to the side and respect the race. And then let the people who are going to race, race. And if the cops came, everybody would leave. I think after our generation, it lost that. Everybody would just race. Hundreds of cars would just line up and race for free. And that's why I actually stopped racing. I'm not going to race for free. It's all about making money back, back when we were doing it.

Oliver: What kind of money... What were the stakes in a lot of these races? How much were you racing for?

Scott: A lot of times it was in the hundreds. Like four or 500, 600. A couple times it got into the thousands. But yeah. I have one race where the guy got me so upset, I raced him for $5. But I just did it just out of... he was trying to punk me in front of my girlfriend back then.

Oliver: But I would think four or $500 in the mid eighties, that's a lot of money.

Scott: Yeah. I worked at GEMCO as a box boy, making seven bucks an hour back then. I even asked myself, how did I come up with that money? So yeah. It was interesting.

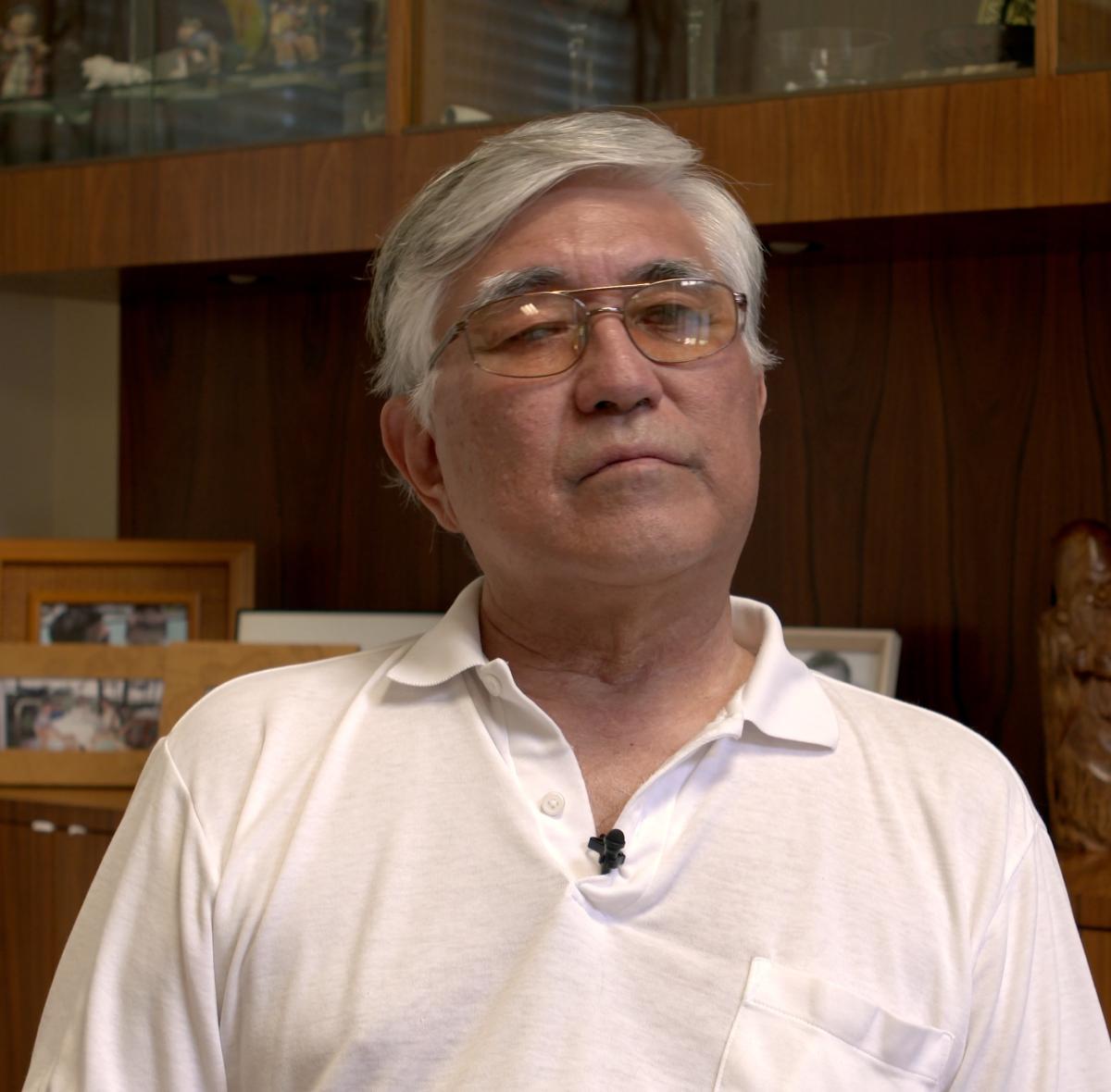

Jimmy Ige

Jimmy talks about the history of the Rising Sun dragster.

Jimmy: My name is Jimmy Ige. And I had a gas station for fifty years, and then I had a repair shop for twenty years, and after that I had a auto repair shop and all that. And that's basically how I got started in automotive field. I'm Nisei.

Oliver: How did you first get interested in drag racing?

Jimmy: Actually, It started about 1965. I built a race car called the Henry J. And I asked Michael to be my partner, and he said, "Yeah." So we had a Henry J. And we had that going out of my gas station. And after that we got promoted to the junior field car.

Oliver: And you mentioned, Michael, can you just briefly mentioned who Michael was?

Jimmy: Michael was my best friend and we grew up since we were twelve years old and we got to be buddies and he was into cars and I was into cars and basically that's how we got started in drag racing.

Oliver: And do you mind just mentioning what his full name was.

Jimmy: Michael Yoji Sassa.

Oliver: Was he also Nisei or Sansei?

Jimmy: Nisei too.

Oliver: So the two of you first started with the Henry J.

Jimmy: Yeah.

Oliver: And just, just to clarify, Henry J. Was the model of the car. So this was a it was originally made by Ford?

Jimmy: Yeah. Uh, it was a Kaiser Fraser. Yeah, it was an oddball car, and it was kind of different and cheap. And so that's how I decided to build that car, because it was unusual too, you know.

Oliver: What motivated you to be interested in building the car and to, you know, get into sort of, you know, drag racing tracks and track stuff?

Jimmy: Originally, drag racing didn't start until 1955 and they had all the types of racing like circle racing and Indy car racing. But I wanted to go into drag racing because it was more amateur. And we did a lot of illegal street racing back in those days. That's how we got started and then it got improved to commercialized drag racing. So that's how we got promoted up.

Oliver: How long did you how long do the two of you race the Henry J for?

Jimmy: Probably about ten years.

Oliver: Okay. So when did you get the dragster is what I want, is what I'm asking.

Jimmy: In 1965.

Oliver: Okay. And where do you how did you find it?

Jimmy: It's a long story, but we went to get safety equipment to drive a dragster, and I asked for a real good deal to purchase a parachute. And he says, "Tell you what, Jimmy, I got a good deal on a parachute" that was white because nobody wanted white. And so he said, "Okay, that's cool." And then I said, "Let's put a zero on there for the rising sun," because being Japanese and all that, and I enjoy my heritage with Japan. He says, "Yeah, that's pretty cool." So that's when we got the name Sons of the Rising Sun.

Oliver: if I recall, though, that was a name that the announcer, the Dragstrip called. They called you that because that wasn't the name that you went with.

Jimmy: No, no. It was the announcer that and he would say, "Oh, here comes the Sons of the Rising Sun." And that's how we got the name.

Jimmy: So we figured it out. So we actually finally we figured it out ourself, you know, and we started getting better and better. And it took us a while, but we we made it on top quite a bit. Yeah.

Oliver: Do you remember the first race where you won with the car?

Jimmy: Yes. That one right there. Lyons. Yeah. Yeah. And the ET, the lap time was eight, eight, twelve. Eight seconds and twelve, eight. And then the goal was to get into the seven second range and we finally made it to the seven second range.

OLIVER: Yeah. So is it that story that that's right there over your shoulder?

Jimmy: Yeah. Yeah. That's one for Yeah. Egan Sasso won. Yeah.

Oliver: And that was from you what, 1967 or ’68.

Jimmy: ’67. Right around there. Yeah. And technically, we've won trophies at Las Vegas. Bakersfield, Lions is Orange County, and that's about it.

Oliver: Yeah. I'm going to go back to something you mentioned earlier, which is when you were buying that parachute, you decided to put the The Rising Sun logo on there. You know, was it important to you and Michael that in the visibility that you had in this car world and the racing world, that you were basically, you know, representing being Japanese? Was that important to the two of you?

Jimmy: Oh, yes. Yes. Because back in those days, all the good stuff was made in Japan. You know, the Sony TVs and all that, and I was proud of it, you know, it wasn't my heritage about it, but I even got a plaque that I want to give to you. It says made in Japan.

And on that on the junior field car, I had it right on top of the engine breather it says Made in Japan. So it meant a lot to me. You know. And I think basically going back to my brother, it was his too because he painted the car yellow and he painted the 100th Infantry on the car. And there was just a carryover from my brother.

Oliver: Was Fred in the Hundredth?

Jimmy: Yeah 442. 100th Infantry.

STYLE

Introduction

Curator Oliver Wang introduces the exhibition theme, “Style”

Cars have always meant more than just a means for transportation. We also love how they make us feel when we look at them or are seen in them, whether sitting at a stoplight or gracefully careening around an asphalt track. From car customization to drift racing, vintage rim collecting to cutting edge auto design, the Japanese American car experience wouldn't be complete without exploring the importance of style, design, and aesthetics. After all, it's not enough to just get you to where you want to go; people want to look good getting there as well.

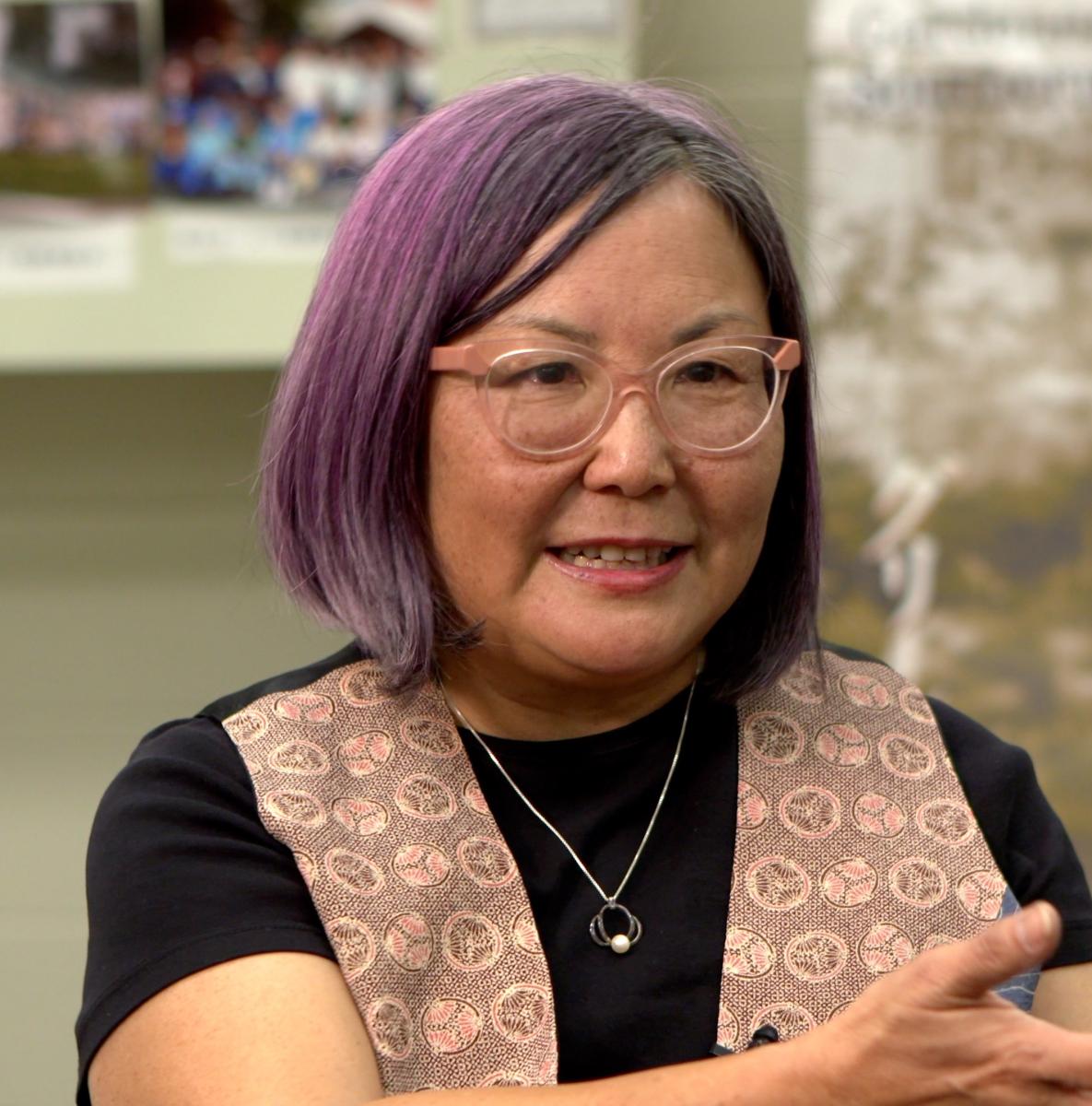

Nadine Sachiko Toyoda-Hsu

Nadine discusses the early drifting scene in Southern California.

Nadine: My name is Nadine Sachiko Hsu. I was born and raised in Arcadia, California and I've lived here ever since like... Oops. I never left. I am a Nisei but remember our conversation that was kind of... Yeah. My grandfather was actually born here in the States but he did go back to Japan and marry and had my dad in Japan in Kumamoto. And then, my dad came here and met my mom so I'm a Nisei-ish (laughs).

Oliver: Right. Somewhere between Nisei or depending on how you want to count it, just-

Nadine: Nisei and a half (laughs).

Oliver: So let's get into your background in cars. And so, how did you... What is your earliest memory of being interested or fascinated in a car?

Nadine: My dad was very into F1. He would read magazines on the toilet of F1 cars. It'd be F1magazines on the toilet. So then, I'd be in the bathroom and then I would read his magazines and I'm like, "Oh, look at these cars. That's cool." Put them away and... I think it was always in the back of my mind. And then, he would always watch F1 and I'd sit down and watch it with him and it was just something that we would do. And then later, I met a lot of people who were into cars and I would go with them to the street races in Ontario. So this was much later, like probably when I was in ninth grade or something and we would go to the street races and I loved it. And there was a woman street racer named Kimbo and she was one of the only females drag racing her Honda Civic. And she really inspired me and I'm just like, "Oh, gosh. That's so cool." She doesn't always win but she's out there giving it her all and she's very brave. So I was like, "One day, I really want to do this. I want to be like her."

So I got my driver's license and immediately started fixing up my car and modifying it and going to Kinokuniya and buying Option magazines which is... They have lots of cars from Japan that inspired me to fix up my 240 and I happen, just by chance, to get a 240 as the first car. A cousin sold it to me for like 500 bucks. It was not my preference. I thought it was a terrible car. And then, I opened up an Option 2 magazine from Kinokuniya and it was like my car all over it and I go, "Oh, I have the best car for drifting," and I had no idea. So I was going to sell it and get a Honda but I changed my mind and I just stuck with the 240.

Oliver: What year was it?

Nadine: 1989. It's a is. I still have it.

Oliver: Okay. There we go.

Nadine: Yeah.

Oliver: Early '90s would've also been the heyday of the import car scene-

Nadine: Mm-hmm. Yes.

Oliver: Battle of the Imports. Things that were basically off the streets but more organized. And then, eventually, you would have the Showoffs and other car shows and car meets. Were you involved in that part of the scene as well?

Nadine: Yes. I would go to Battle of Imports, actually with my girlfriends. We would have fun there. And also, Pomona, they would do drag racing, just practice. I would go to that and actually that's where I had my first race, like where I took my own car, was the Pomona Raceway. And then, I would go to Ken Miyoshi's Import Showoffs all the time. I love looking at all those cars.

Nadine: So in terms of mods for my 240, the first thing you have to do is lower the car. I didn't have any money, so I cut my stock springs to lower my car, made a huge mistake, lowered it too much, got wheels. So I think suspension and wheels was like you have to have. That's kind of the base, the default. And then you get into stickers and then you get into mufflers to make your car sound good. That's kind of where I was hovering for a long time. Because I know my story's a little bit unique because I came from loving car shows, but also loving races. So when I initially built my car, it was for car shows and then I realized, "Oh jeez, I can race this car too." But it was automatic. And then I'm like, "Well, I'll just try automatic, but I think I need to change this car to stick." So then later I met Benson and I was into drifting, my car was still automatic, I got to swap this out. So we actually swapped our engines with a Japanese, it's called a SR20DET. Basically, a 240 in Japan is a 180, so it's a 180SX engine. So I put the engine that should be in my car, because in the USA you get these crappy truck engines instead of the turbo engines. We swapped that and I made my car five-speed and that was the best thing. And then after that, I built the car for race, for drift. And then that's kind of where the other piece of the pie is for me. But I've always been known to have a beautiful-looking show car that also is a race car. That's kind of unique for me because many people just build their car with one thing in mind, not both.

Oliver: Right.

Nadine: And I was always kind of...

Oliver: Try and do both, right?

Nadine: Yeah.

Oliver: Yeah, so let's get into this. You kind of explained how you first got into racing, but then how did you specifically get into drift? And actually before you get there, just for the benefit of our audience here, can you just define what drifting is and what makes it different than other forms of car racing?

Nadine: Drifting is sliding your car so it looks out of control, but you're in control 100%. It's something that people associate with ice skating, like ice skating your car. What's different from drifting than regular racing is it's not time-based, it is style-based, very subjective. So if you go into drifting competitions, many times it's in the eye of the beholder who's the winner. It's not necessarily like a time. It's a score from a panel of judges and what one judge may like, the other may not. It's still a technical sport because there are certain things you have to do to score points in competition. But it's an art and it's so much more interesting to watch than drag racing, because drag racing is just it's over in a few seconds and then you just have a time and that's it. It's very cut and dry, black and white. But drifting is it's an art and it's subjective and what one person thinks is an amazing slide, the other one may think differently.

Oliver: What was your introduction to drifting and what about it clearly captured your imagination?

Nadine: My introduction to drifting was through the magazines at Kinokuniya. But it was really funny because I didn't know what I was looking at. So I saw it and I read the magazine and the cars were this way, they were kind of sliding. It was action shots of the cars and I'm like, "Why do they keep taking pictures of them?" And I didn't know. I didn't know what I was looking at, but I was like, "Oh, that's cool, but I like his wheels." And then I met Benson at a 240SX Owners Club meeting and then he turned me on to Option videos instead of Option magazines, but they're videos at Kinokuniya. And then we started watching the videos and I'm like, "Oh, that's what drifting is." He introduced me to that and eventually we started going to the mountains and racing our cars in the mountains.

But that was more just like grip driving. That wasn't drifting. But we were drifting somewhere in the mountains a little bit. And then they started having sanctioned drifting events here. That's when Benson invited me to go watch him. But I was like, "You know what? I'll just bring my car," because I have the perfect car, like the Honda Civic of the drifting. Because in Honda Civics, they were great for the drag racing and the car shows. In drifting, you have to have a 240 or a Hachi-Roku, like a Toyota Corolla. Those are the quintessential cars to have.

Oliver: Why?

Nadine: Those are the cars that our founding fathers of drifting—like our founding father of drifting founded drifting in a Toyota Corolla back in Japan in the '80s, so number one. Number two came later in 1989 with the Nissan 240. That also in Japan, the earliest drifting competitions and videos, the 240 was there. Those were the main two cars that you would just see all the time in the videos. And 240 is much easier to drift than a Corolla.

Oliver: Right. I was going to ask, is there something inherent to the design of the cars, the way its chassis is built, handling...

Nadine: Yeah.

Oliver:...that makes them particularly good for drifting?

Nadine: I think the wheelbase and the fact that it's rear-wheel-driven and it's nimble and light all play into that, definitely.

Oliver: As you were saying, when drifting first came up to Southern California it was mostly being done kind of like unsanctioned, off-the-books, up the mountains.

Nadine: That's right.

Oliver: So what were the main areas that people would go to drift up there?

Nadine: Well, see the drifting, a lot of people would just drift on the streets. If you're talking about drifting only, there's a lot of people that would drift in the street wherever they could find a turn where there was no one around at night. Because, see, drag racing, it was very organized chaos because everyone knew where to go. But with drifting, it's kind of like people just make up, find a street, and go with maybe two friends. That's what also is very different about drifting is we were just trying to slide anywhere we could. We'd find a parking lot, a street in the industrial area. That was mainly the place where you would see the illegal drifting.

But that was very short-lived, because there was like Moto Miwa of Drift Association. He founded Drift Days very, very early. I think 2001. Was it 2001, Honey Bunny? Moto? I think the very first Drift Day was like 2001. He did Drift Days at Irwindale Speedway in the parking lot. So he got the drifting off the street. Moto was a big organizer of Corolla Owners Club called Club4AG. Moto was very, very important because he brought drifting off the street and onto the track.

Oliver: What was the importance of making that transition?

Nadine: Because it's dangerous and I think drifting could not ever be where it is today in the United States if it wasn't a legitimized motor sport. I think it's always struggled to be. So the sooner we got it off the street, the more likely it would become a more legitimate motor sport. Because now there's a professional series called Formula DRIFT, and Toyota backs my friend who is a driver. So it's like, then you have the big sponsors coming in and it's a sport that you can make a career out of.

Tats Gotanda

Tats talks about how he transformed his 1959 Impala into the Buddha Buggy.

Tats: My name is Tatsumi. I like to be called Tats Gotanda.

Oliver: And what generation Japanese American are you?

Tats: I think I’m Sansei.

Oliver: So Tats, how did you first become interested in cars?

Tats: I don’t know. I guess through magazines and... I used to see... I don't know if you know Bob Hirohata, I used to see his car and from there, I just decided I want to just start customizing cars. It's just mild custom and don't ask me how I got to where it is with the finished product. But I just kept on going and before I knew it, it was a show car. And little by little, that ’59 Chevy was getting, what I consider as a mild custom. And then, eventually I started changing the grille on that thing and the tail lights and body modifications. Taking the door handles off, putting on air scoops, sunken antennas, pipes on the side. And it got to the point where, in fact, I was sort of scared to drive it. So I got a ’55 Ford and I modified that thing. That's the car I was driving out in the street. In the meantime, my Chevy was with Bill Hines and he was constantly working on it.

Oliver: This is the Impala, right?

Tats: Mm-hmm.

Oliver: Tats, you were saying, with every car that you had, whether it was the ’50 Merc or the ’55 Chevy, obviously, the ’59 Impala, you would always change something. There would be some kind of customization. So why was that important? Why was it important to do any kind of modification or customization?

Tats: I just love custom cars. I just want something different. I'll be honest with you, I thought I had the baddest car around, okay? And so, I would love to show that car off and when I did, it was a showstopper out in the street. And a lot of the custom cars was done by Barris. Barris, Barris, Barris this, Barris that. And then, I found out he worked for Barris and I said, "Man—"

Oliver: He's got to be good.

Tats: —"He got to be good." Yeah.

Oliver: Yeah.

Tats: And he was good.

Oliver: And so, you worked a lot with Ed Martinez on the interior. So how did you first start working with Ed?

Tats: It started with my Chevy. My ’59, when I first got that Chevy, I said, "Could you put the tuck and roll dash on there?" And I want tuck and roll on the rear window and so he did it. And then—

Oliver: This is the ’59 Impala?

Tats: Mm-hmm.

Oliver: So this is the Buddha Buggy?

Tats: Right.

Oliver: So what were the first things that you began to do in terms of the modifications on the Impala?

Tats: Take the emblems off.

Oliver: Okay.

Tats: I started taking the emblems off. Well, the first thing I did was lower it. And next thing I know, I went to see Bill Hines and I had him put in a sunken antenna and that was the next. Well, I remember I had Bill do the tail lights. And then, I had him put some air scoops on the car. So at the same time while it was there, it went over to Martinez. I said, "Hey, a poster, I want it all white," so he posted that.

And then, it would go back to... He started doing something else again. I remember when he took the door handles off, I said, "Hey, Bill," I says, "I want to put the button on the side," I said, "but how could I use.... For security, I want a lock and key." He says, "We got to..." He said, "We have to use a ’51 Ford glove box lock." So when he pushes the button, he says, "This thing would trigger or tap something," he says, "then the door would pop open." I said, "Really?" He says, "Yeah." But anyway, he did install it exactly where I wanted it and it worked. God, it was amazing. Uh-huh.

Oliver: Now, at what point did your Chevy get the name Buddha Buggy? Where did that come from?

Tats: I started thinking about that. I said, "How did I come up with that name, Buddha Buggy?" I don't know. I think I was with Bill Hines and I said, "I'm going to put this in a show." He said, "You are?" I said, "Yep." And then, I started thinking, "Man, I got to... Maybe I should come up with a name," and I started thinking a different name. Then finally I said, "You know what? I'm going to just call it the Buddha Buggy," I said, "Heck with it," and there it was. And then, I had a poster made Buddha Buggy and all the things that was done that was modified on the car. I can't think of what the other names that I came up with. That was the only one that stuck with me.

Oliver: So what gave you the idea to enter the car into a show?

Tats: I don't know. I thought it was... When I got down to a certain point, I said, "Maybe this could be a showpiece." And there was a car club called... I think it was Triton. Triton Car Club? And the big promoter name was Gary Canning. In fact, I think his name was Gary Canning.

Oliver: Mm-hmm. Yeah. It was.

Tats: And then, he called me up and he said, "Hey, I heard you got a ’59 Chevy." I said, "Yeah." And he says, "Why don't you put in a Pasadena show?" I said, "What Pasadena show?" He said, "We're going to put on up a show in Pasadena." So he sent me a sheet to fill out or whatever, car, and I said, "Okay." That's about it. That's the first time I started in any shows, was the Pasadena show.

Oliver: What year was this?

Tats: God. I think ’60? I'm just guessing. ’60? ’59? ’60, I think. I think.

Oliver: Yeah.

Tats: Possibly ’61. I don't know. It was in there.

Oliver: And this was the first time that you had any car in a car show like this?

Tats: Yep.

Oliver: So at the Pasadena show, how did the Buddha Buggy do?

Tats: I got first place on that one.

Oliver: Okay.

Tats: In fact, I got first place... Either first place or sweepstakes on every show that car entered.

Oliver: I mean, roughly how many shows did you enter the car into?

Tats: I keep thinking it was either twelve or sixteen shows.

Oliver: Wow.

Tats: ... and I ended up something like twenty-five trophies.

Tim Mochizuki

Tim talks about getting your car ready for cruising Nisei Week.

Tim: Good afternoon, I’m Tim Mochizuki, I’m a third generation Japanese American, actually, of rarity, I’m a native Los Angelan. My mother always jokes that I’m a Nisei Han because she was born in Japan. My father was raised here as a Kibei Nisei, but part of his upbringing was in Japan. Born in Culver City, raised in Gardena, currently live in Torrance, California.

Cruise. You’re part of a car club, you want to see other cars, what did you do? The cruise circuit. The cruises all started right about early spring. Hanamatsuri, Cherry Blossom festival. It’s the spring festivals that the JA community holds. The last cruise here at Nisei Week, end of summer. So, you had that whole spring to summer time. Three months.

If you go back and talk to some of the people, ask them, “What did you do, when did you start working on your car and what was your goal?” And you’ll always hear, “To cruise Nisei.”

The first cruise or the first carnival was either Venice or maybe it was at the time Long Beach, did have an Obon. And all the Buddhist churches published the schedule of when the Obons were. That became the cruise calendar. And if you look, the last thing on there is Nisei Week. So you had a lot of people that started working on their car on the first cruise. And you’d go out to the first cruise and you’d see dented cars, primered cars. No one has wheels. They’re freshly lowered. Exhausts are hanging on the ground, cracked windshields, you name it. By about the middle cruise, which is usually OCBC, the cars are starting to get painted. They’re starting to show rims and tires. They’re starting to have tinted windows. There's some pride being shown. Because everybody was gearing up to cruise Nisei.

And you’d start noticing somebody’s car. You knew someone, “Hey that’s Mikey, he’s getting ready, he’s got his car out.” And then you would see it at every cruise thereafter. Something else was done to it. And after a while you started noticing certain cars and you kept your eye out, because you thought, That’s going to be a good looking car. And when it showed up at Nisei, it’d be fully painted and it would be a fantastic vehicle to look at.

Bob Mochizuki

Bob talks about his father’s love of customizing cars.

Bob: Bob Mochizuki, I’m a senior lead designer at CALTY Design Research in Newport Beach.

Oliver: And can you explain what CALTY is?

Bob: CALTY is Toyota’s Southern California design studio that they started in the seventies. Yeah, they wanted to do something. We just celebrated our fiftieth year, and they wanted this special California vibe because it's the capital car culture of the world. So yeah, they set up shop here and we've been designing Toyota Lexuses for fifty years.

Oliver: What generation Japanese American?

Bob: Yonsei.

Oliver: Where did you grow up, and from what you know, how did your family end up settling there?

Bob: So I grew up in the San Fernando Valley and now it’s called Northridge [or] North Hills before [it was called] Sepulveda. Yeah, good question. Why did my parents land there? Well, my dad grew up in the San Fernando Valley. They both went to the San Fernando High School. You know, they all had different histories before the war, but they both ended up at San Fernando High School. And my dad started a machine shop in Van Nuys.

Oliver: Did your parents also grew up in the valley, or they grew up in a different part of LA?

Bob: Yeah, they were both born and Terminal Island.

Oliver: We’d love to talk a little bit about your your dad and what you knew about him in his days. And first of all, what was your dad’s first name?

Bob: Kiyo. Kiyoshi.

Oliver: So, he grew up, as you said, in the Valley. He went to San Fernando Valley High. And, was he was in a car club back then?

Bob: Jr Decoyos, So I guess that means roughly in Japanese, like, come out and play.

Oliver: How did your dad get interested in cars?

Bob: Oh man, I don't know, but my guess is after the war. This is just my guess: these guys are probably pissed off or I think they wanted to assimilate really quick. And if you saw pictures of my dad, it looks like Grease. All of his friends. Hey, (laughs) so I think that was a driving factor. I think my dad just had a—always interested in machine things because he loved motorcycles, he loved cars, airplanes, and all his friends seemed like the same. But my gut is that it was a kind of a We'll show you guys, you know, we're American, too. And my dad always had that kind of attitude.

Oliver: And at a certain point and I don't know if this was his early as high school or maybe just after high school, but he got interested in customizing cars.

Bob: Yes.

Oliver: Yeah. Tell me more about that.

Bob: Yeah. Again, from what—I wish I listened more with a bigger, finely tuned ear, but he'll tell me stories how Valley Custom—he'll go there a lot with his friend Tad Hirai and they'll do insane custom jobs that, you know, don't even consider doing it by yourselves in a garage now. But they'll do it all themselves. And, you know, my dad can shape metal, too, like a show car quality, and all his friends did too.

Oliver: Do you get the impression that it wasn't like a lot of the JA guys that were growing up in the valley in the 1950s were really into this culture of like the customization.

Bob: It sounds like a lot of them because yeah. Yeah, again, like Horse, Terry called him Horse, and it wasn't till later, you know, I see him all the time and say "Hey Horse." My sister worked part time for my dad and it wasn't till later, much later that I saw his cars online and his picture online, I go, "Oh, crap."

Oliver: Do you know what kind of cars your dad was customizing back then? Like his own cars?

Bob: There are so many.

Oliver: Wow.

Bob: Yeah. This is like Chevys to Mercurys to Lincolns, and over the years he was constantly, yeah, messing around with cars.

Oliver: What was it about customizing cars that was so appealing to people? Like what did people get out of it?

Bob: Yeah, for me it's, and trying to understand what they I'm sure they thought the same way, it's is doing something to show off that's yours. I created this I knew how to do this and it's, you know, flexing. They're showing how badass you are, you know, as that happens today, you know, And I think it just comes out of then I like showing off for girls (laughs). It just comes out. I always even when I was growing up.

Oliver: It's, I mean, the perception I have is it's a means of, and this is not, again not unique to this era, not unique this community. But cars are this very powerful way people can express themselves creatively.

Bob: Yeah, definitely. And especially back then. I mean, the work custom work that they're doing is is incredible. Like. But yeah, it's all creativity. It's all putting your personal stamp on something and yeah, it's loud, it's colorful. It's stuff kids dream about it.

Oliver: Right? It's like a piece of art except that you get to drive it down the street.

Bob: Yeah, you show off. That's all of showing off to other people, right? Yeah, so he did aerospace parts. I think all these guys are drafted in the Army, you know, shortly after they graduated high school. And like my dad and his partner, Jimmy Hanamoto, they learned the machine trade in the army. And my dad was based down in Florida on the desert. And yeah, he worked in a machine shop. And then naturally, they opened up, bought their own shop right by the airport. And yeah, he did that until my dad retired late, but early 2000.

Oliver: Okay, Got it. And you know, deep into his, like, adulthood, like basically throughout your childhood, you were in a lot of cars coming in and out of the house.

Bob: Yes. Motorcycles. He he raced more motorcycles in the desert. Yeah. Cars constantly changing from Cadillacs in the seventies. Then he got into German cars and it was BMWs and Mercedes. And he had a Triumph TR4 he got in 1969 and he fixed it up a little bit, but he had that until he retired. I wish I grabbed that sucker.

I was lucky enough to grab one of his motorcycles. He restored a BSA that looked like junk, but he restored it till like mint condition. And I thought, you know, in his late seventies, I figured I'd better talk to him about keeping the motorcycle. So I'm glad I still have it. And then I'm going to carry it around, you know, take it to my homes until, I don't know (laughs).

Oliver: So in terms of your own background. So yeah, what was your introduction and how did you get turned on to the world of cars? Was it through your dad or was it through some other?

Bob: I think it was through my friends because maybe in late junior high, early high school, they started getting into Volkswagens, which was yeah, for some. Then I caught the Volkswagen fever back then.

Oliver: So what was it, What was your first car?

Bob: So I shared my brother's Honda Civic for a while and he had a old, cheap, old Mustang. But then I was lucky. My dad, you know, he supported me. I mean, maybe he didn't talk much about it. I mean, my dad can both share with anybody for hours, but he wasn't so much talkative. But, you know, he supported me.

Bob: He got me a brand new VW Golf, $13,000.

Oliver: What year?

Bob: ’87 or ’88. ’88.

Oliver: So what was the appeal of VWs back then? Is it easy to modify?

Bob: It was easy to modify and clean, and there's all these shops where you can modify them. And then we'll go to these VW shows and do cruising, and yeah, I'd enter car shows and I got in a couple of magazines

Oliver: I'm just wondering, when you were growing up, you know, especially, let's say, through high school, right. You've already been introduced into the world of cars. You got this VW craze you're interested in, you know, and you've seen your dad hang out with him and his friends, maybe hearing some of their stories, et cetera. Did you perceive growing up, did you feel like there was something distinctive about like a Japanese American car culture that existed?

Bob: Yeah. So when I in high school it first started with a couple of my friends, but then when I, yeah, joined the fraternity that started really became exposed to the Japanese American/Asian car community.

Oliver: And what helped define that? Like, what were the particularities of that been different than the other car companies?

Bob: That's a good question. Yeah it's a—hmmm. Well, it was real cliquish. Yeah, apart from the fraternity, you have these different car clubs these guys would be part of, active members. And to me, you know, I'm sure there's a lot more history, but to me was news. It was like, What? There's San Gabriel? There's a big car club? Yeah, what are you talking about? You know, hundreds of people that meet up there. There's a term for that but yeah, I started going to those with all the Asian people (laughs) but all my friends, yeah, we're there. We even participate in the races.

But yeah, I guess my point was, once you're in it, it was like huge, like from Orange County to South Bay to San Gabriel. Yeah, I guess I'm surprised of the scope. During that time they would, if I'm not mistaken, they'd throw dances at a club with a deejay. So that was another whole social thing because all these clubs, you have to go on the weekend, and then you go to these races also, and then you go to eat at this other place (laughs). It was fun.

Oliver: I just wanted to circle back to the question I asked you earlier about whether or not you thought there was something distinctive about like the JA car scene that was different than the other car scenes you were around.

Bob: I think back then that the German crowd was doing more performance looking and the JDM crowd, you know, they're so low to the ground. But again, I don't know, there's all different tastes, like my friends have these fast MR2s. But yeah, to me it was like Asian overload.

WORK

Introduction

Curator Oliver Wang introduces the exhibition theme, “Work”

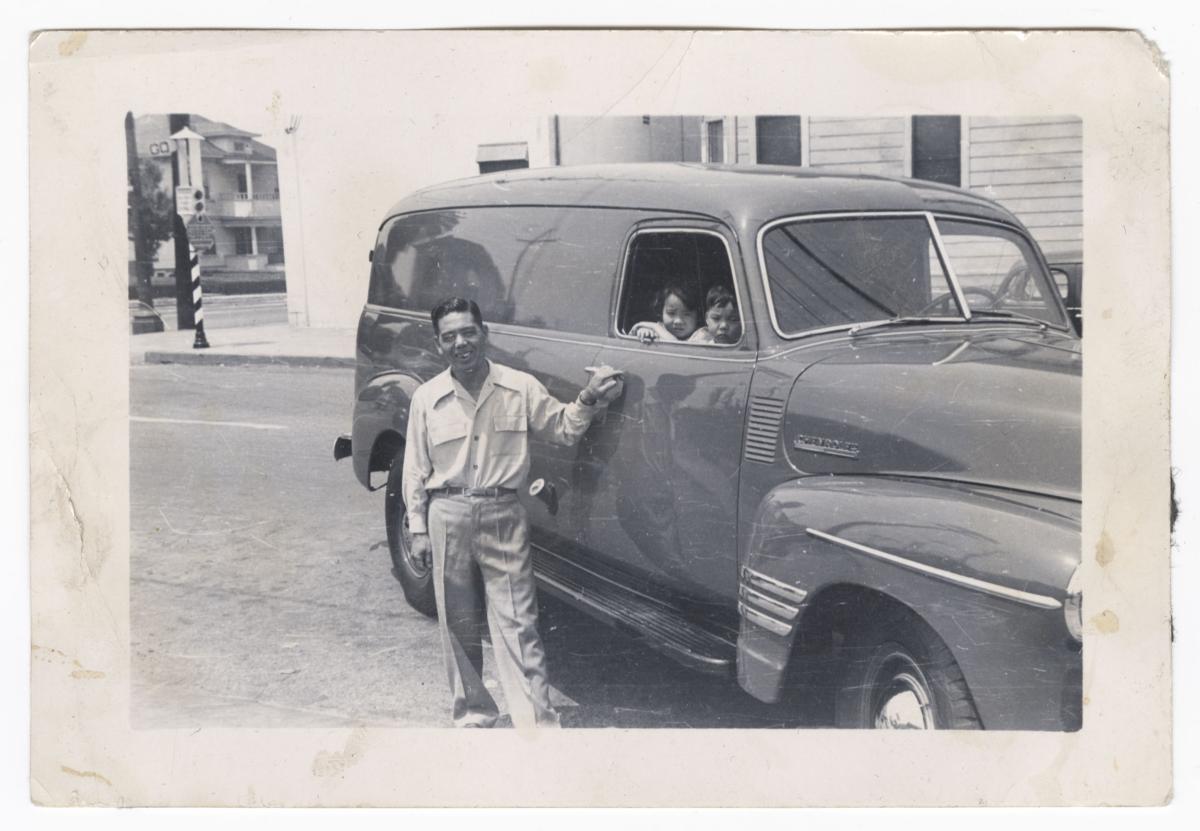

Work vehicles have been vitally important to the survival and growth of the Japanese American community throughout the entire 20th century. Especially with racial discrimination limiting labor opportunities for many Nikkei, work trucks and vans opened up forms of self-employment that allowed families to pursue social mobility on their own terms. That included farming, gardening, fish peddling, and service stations, all areas of work made possible by cars and trucks. These vehicles may have been more humble in their looks, but they were no less profound in their impact on family and community fortunes.

Naomi Hirahara

Naomi recalls memories of her father’s gardening truck.

Naomi: So Naomi Hirahara and I grew up in Altadena, and then we moved to South Pasadena, and I live in Pasadena right now.

Oliver: And what generation Japanese American?

Naomi: I call myself 2.5. My father's a Kibei Nisei, and my mother is a Shin Issei. They're both atomic bomb survivors, so that's part of my legacy.

I guess my family, my parents, it's kind of a picture of the past because they were omiai or arranged marriage. My dad was here. He was born in Watsonville, California, went to—uh, with his older siblings to Hiroshima when he was a child and then, you know, was in the train station when the bomb was dropped.

And then when he was an older teenager, about eighteen years old, he was—because he only had American citizenship and he did not fight for the Japanese. So he was able to get on a boat with other young men and return back. And so he did farming in Watsonville. He was a migrant farmer and all that. But then there were opportunities in Southern California for Japanese Americans, Kibei Nisei to become maintenance gardeners. And it was actually a very lucrative profession. After World War II, one out of ten Japanese Americans were in the gardening trade. It paid better than other kinds of transitional work.

So, um, but my father was not in camp, but he, you know, kind of rode the wave of gardening. And then in his thirties, he needed to get married. And so my father's family knew my mother's family. So, you know, it was it wasn't like a picture bride situation. The families knew each other. My dad went to Hiroshima and then my mom, you know, they came back married. And, you know, in Pasadena, there was a lot of people in need of gardening. I mean, historically, it's a wealthy area.

Oliver: A lot of lawns.

Naomi: A lot of lawns. And after World War II, with the GI Bill, there was this huge demand for gardeners. There were lawns, you know, outside of all these new developments. So a lot of people got involved.

After World War II, I mean, people are released from camp. They’re barred from doing a lot of different kinds of profession and they need to make money quickly. There’s also a stereotype. There’s the halo effect that Japanese people could grow things. Some of it was based on, you know, fact, because many people, like before World War II had come from agricultural backgrounds.

Oliver: Sure.

Naomi: And that’s actually why a lot of—there’s a lot of Japanese American gardeners, because one was, they had experience working with agricultural cooperatives back in Japan. So they kind of were able to band together. It was not, you know, uncommon for them to work together, whether they’re people in the same profession and like to get good deals, like on fertilizer, whatever you need to do.