1942–1943

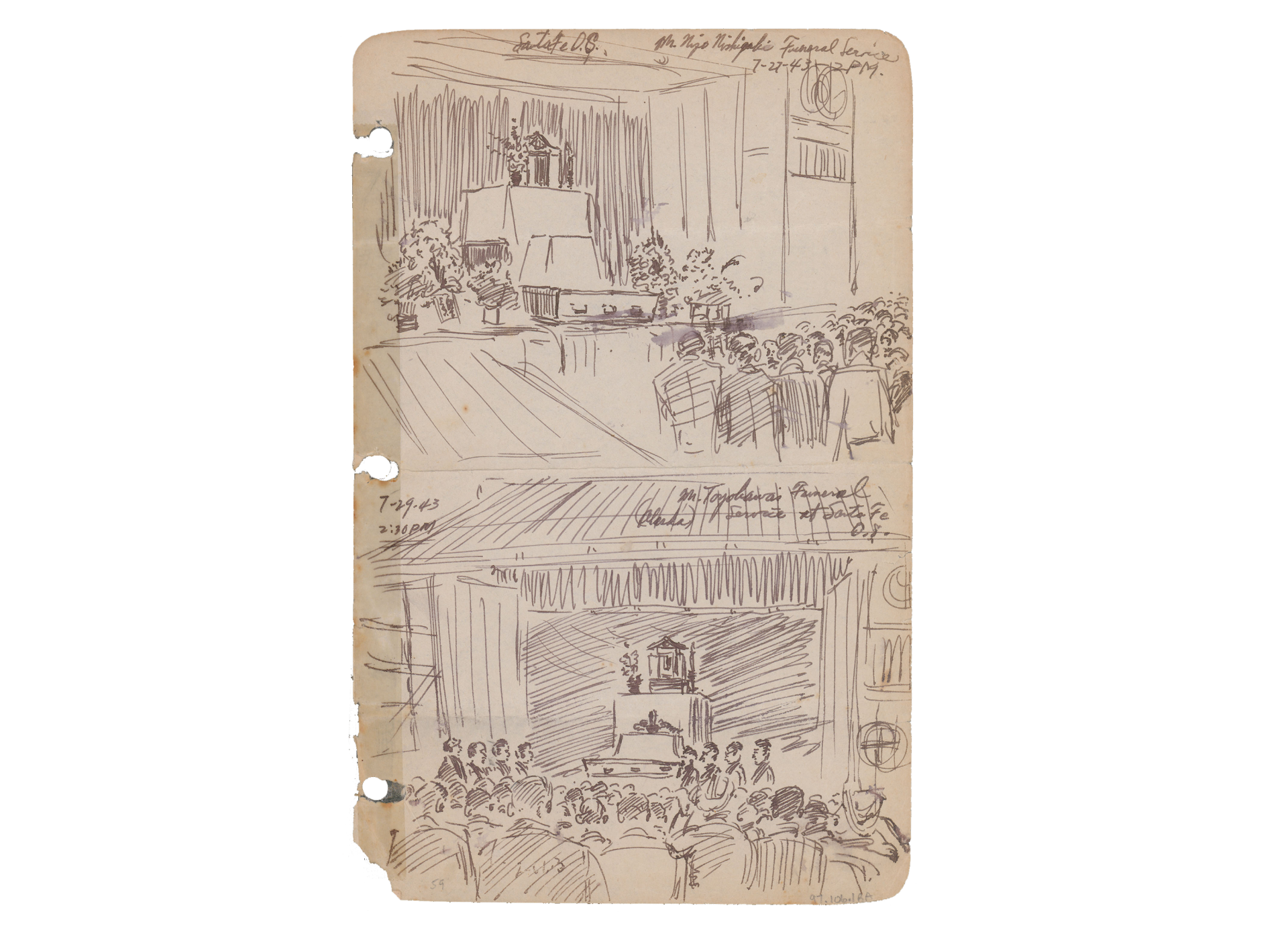

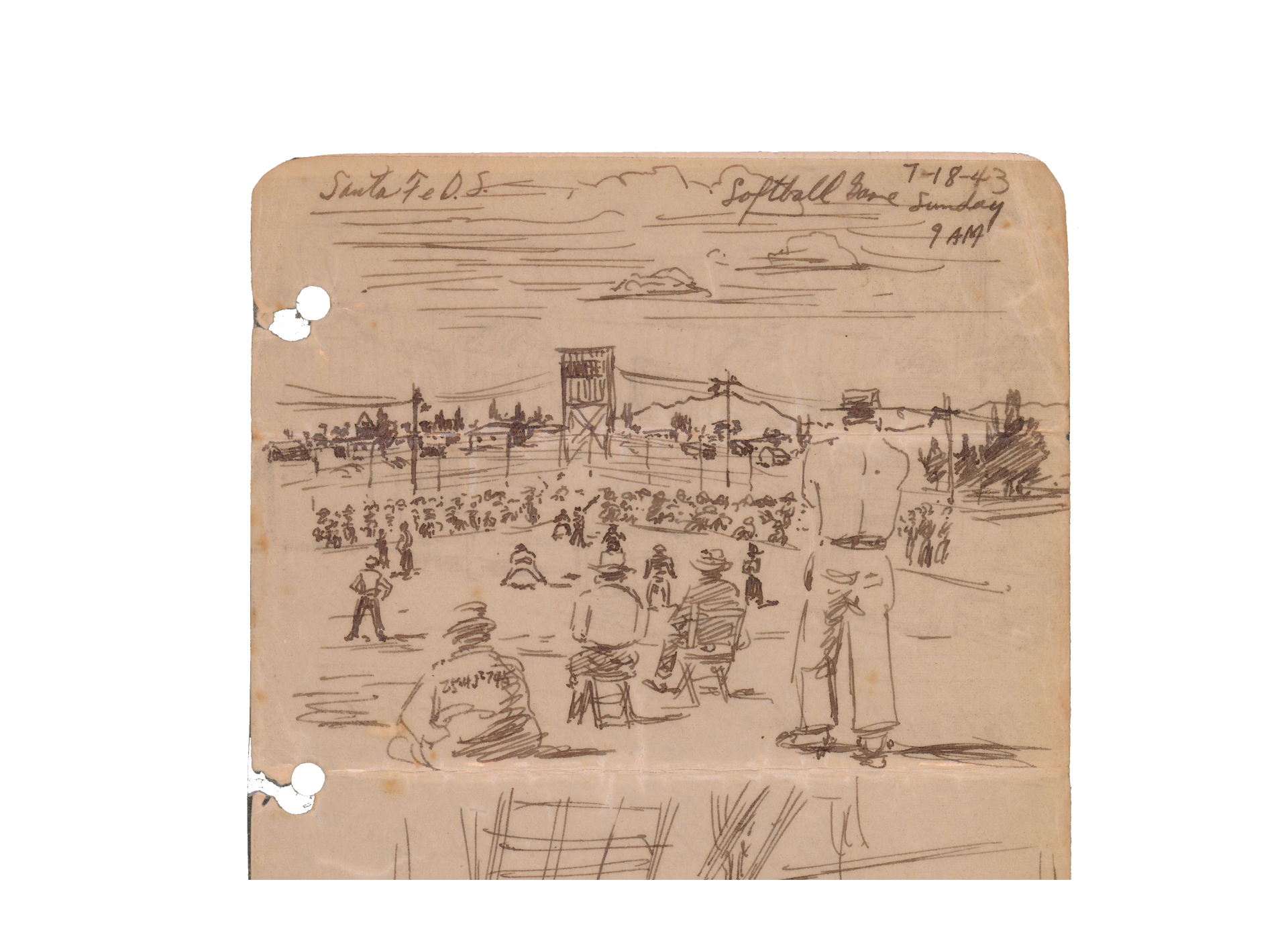

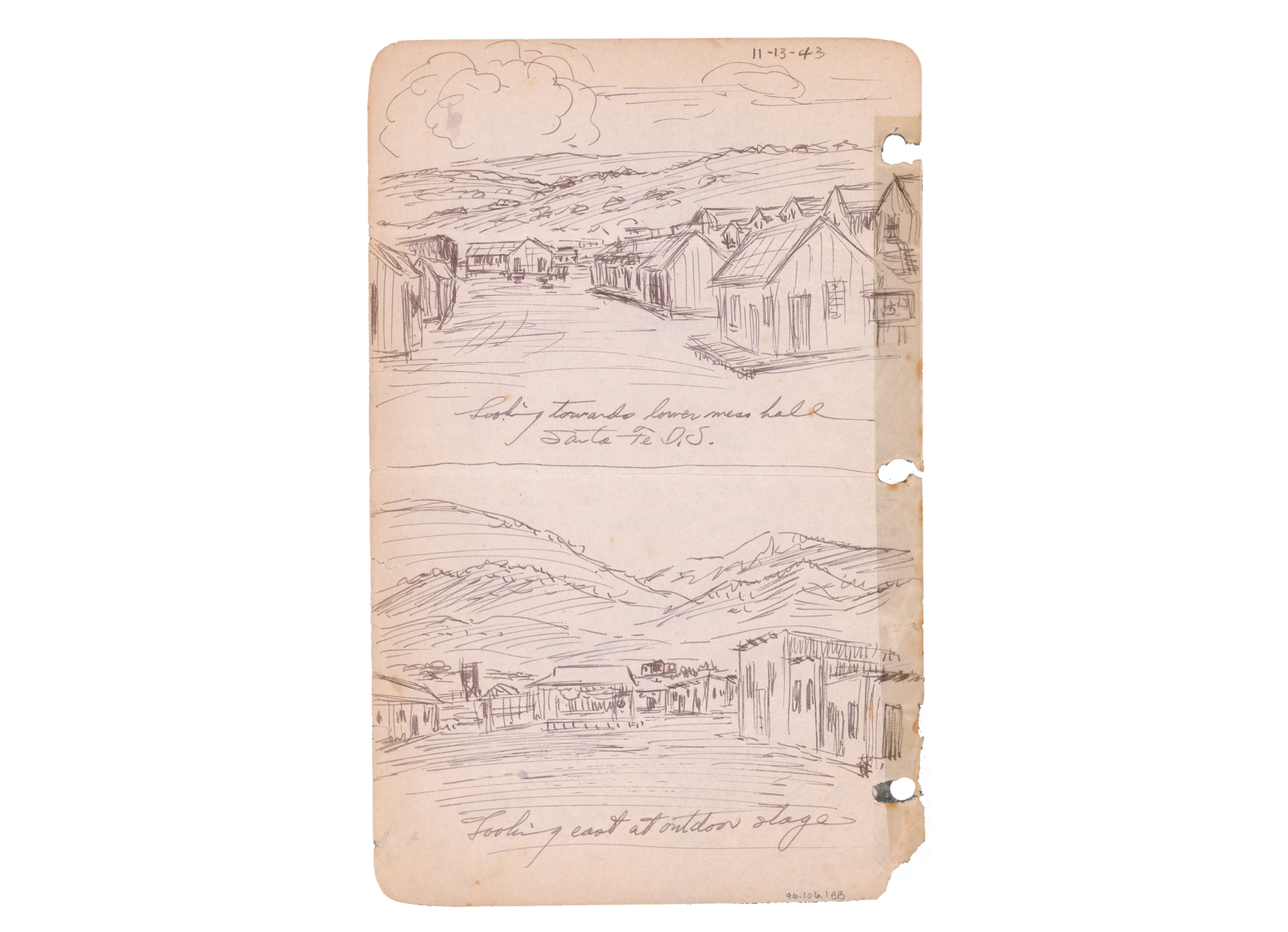

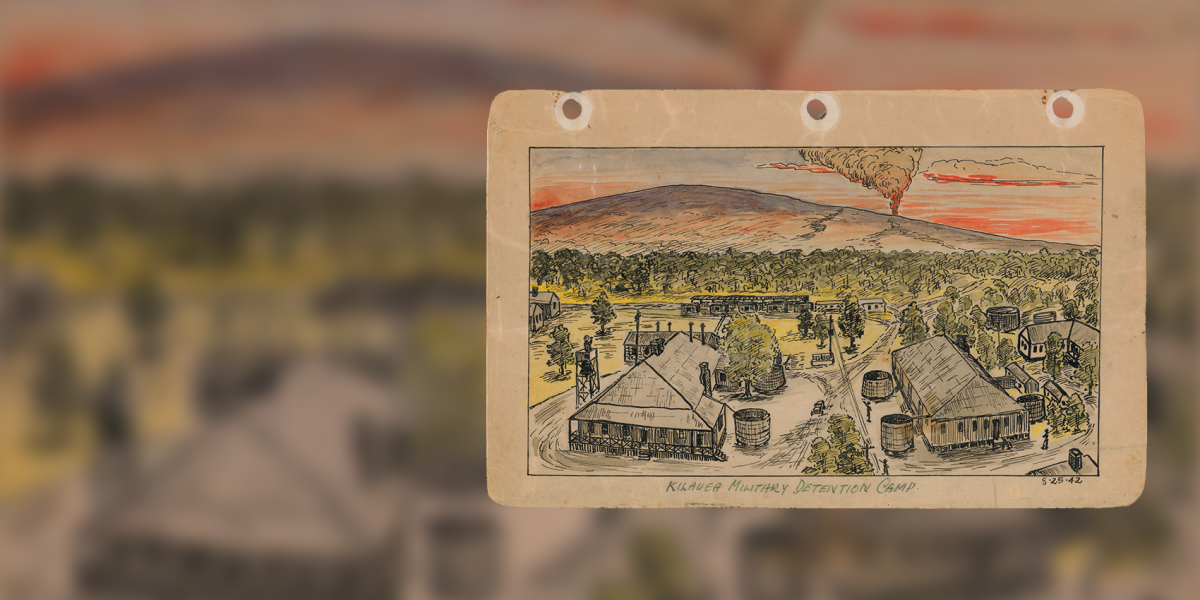

About 800 internees from Hawai‘i were incarcerated at the Justice Department internment camp at Santa Fe, New Mexico. After Lordsburg, Hoshida was sent to Santa Fe where he continued to draw and paint in his notebooks. Art was a way for Hoshida to productively focus his energy away from this disheartening situation. Hoshida and his wife, Tamae, wrote letters to each other almost every day. She would also send him art supplies and items from the Sears & Roebuck catalog. The Hoshidas would have preferred to correspond in Japanese, but in order for the letters to be censored by authorities they had to be written legibly in English. They made several appeals to be reunited at a camp where families could be together.

Most of the men of this camp were Issei and middle-aged. The camp was relatively peaceful, but inmates were kept separate from their families and the reuniting process was very slow. Hoshida also grew impatient and had considered repatriating to Japan—not because he disliked the United States but because he simply wanted to be with his family. However, his wife and brother convinced him to abandon this thought. After nearly two years apart, the Hoshidas were finally granted permission to be reunited at the War Relocation Authority concentration camp in Jerome, Arkansas.