1944–1945

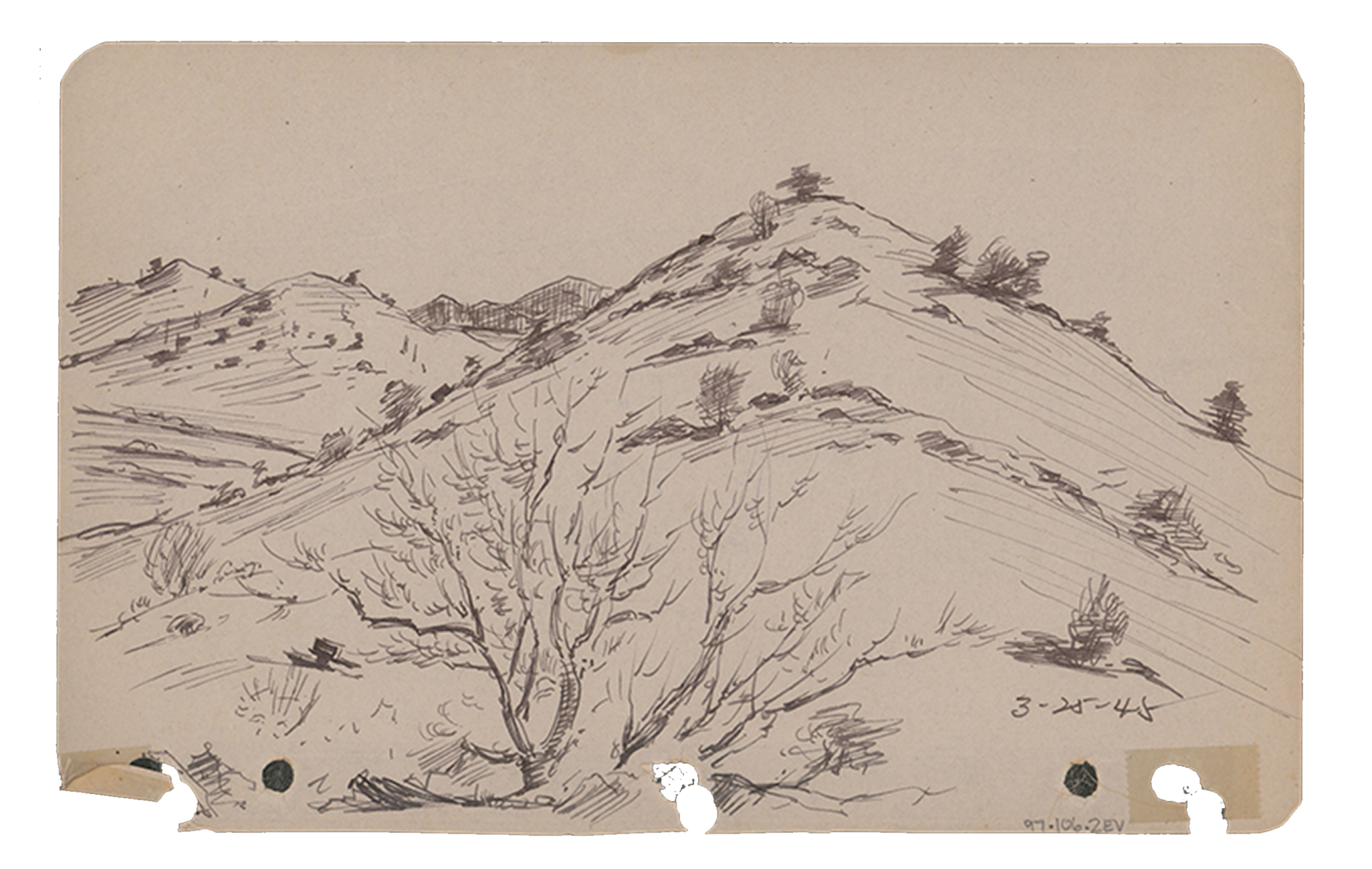

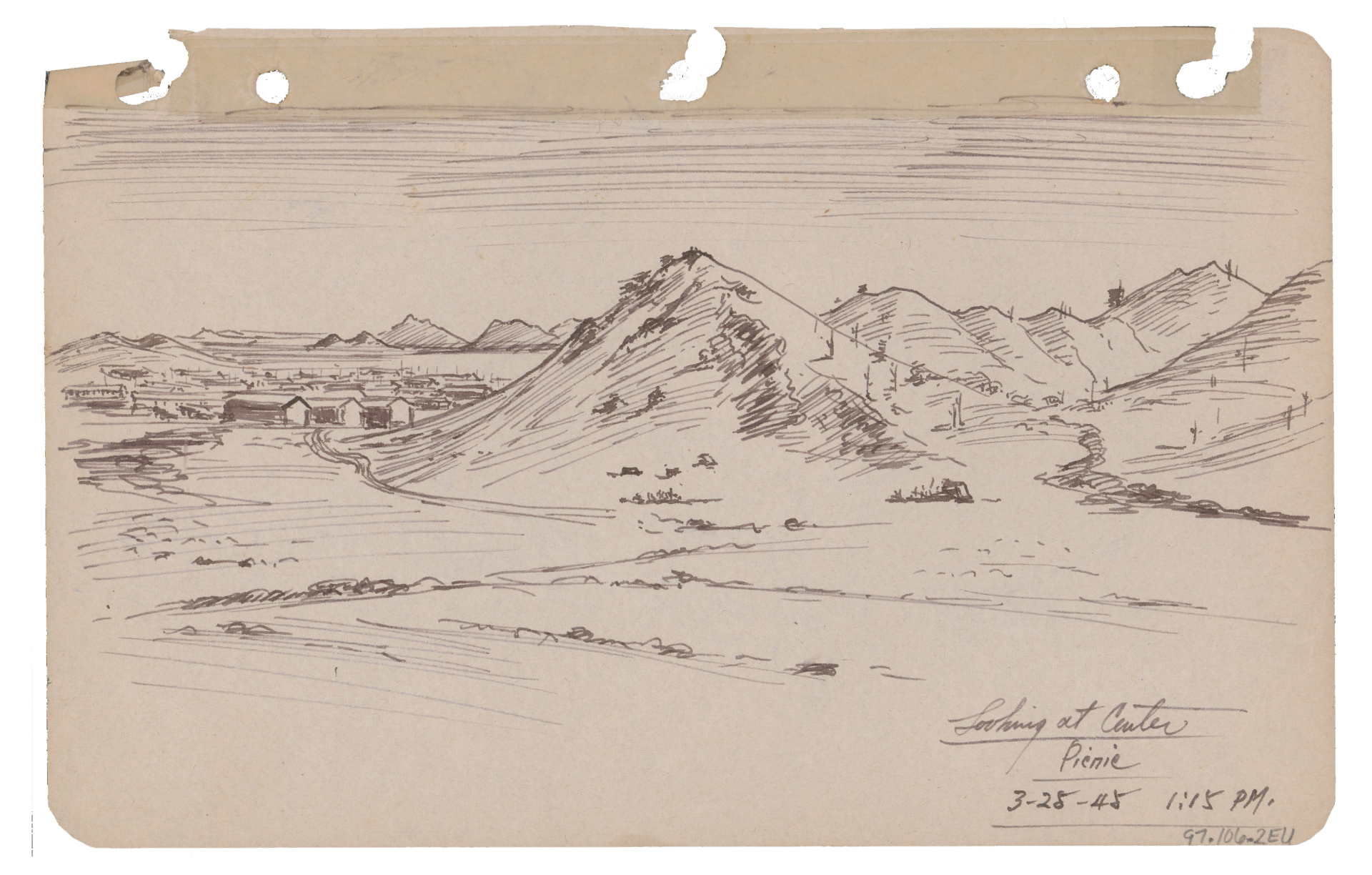

After Jerome Relocation Center closed at the end of June 1944, the Hoshidas were transferred to Gila River concentration camp in Arizona. George Hoshida and his family would remain at Gila River until it closed on September 28, 1945.

Hoshida and his family ended up being assigned to the larger of the two camps, Butte, in Block 61. Utilizing his carpentry skills, Hoshida obtained a large fan to create a cooling system to keep his family comfortable in the scorching Arizona summer heat. Hoshida found work as a pantry man in the mess hall and was later promoted to cooks helper. When not working, he found time to enroll in the Deforest Courses in Electronics, TV and Radio Servicing and Repairs where he learned electrical wiring. Hoshida later used his new talents to build a radio on which the family listened to popular shows of the day, such as the Lone Ranger.

Life at Gila River was easier and more relaxed for the Hoshida family since the absence of restricting fences and guard towers allowed for greater freedom. Personnel managing the camp were more sympathetic and understanding and inmates were allowed to shop in Phoenix and to have picnics in the desert. However, whatever sense of normalcy Hoshida was able to create at Gila River was not to last long. On July 22, 1944, Taeko, Hoshida’s oldest daughter, died after suffering a convulsion in a bathtub in which she was unintentionally left unattended in Waimano Home on Oahu.

George Hoshida and his family left Gila River in November of 1945 for Santa Ana, California where they lived across from an airfield and blimp hanger for three weeks. In December of 1945, the Hoshida’s returned home to Hilo, Hawai‘i, debarking from Wilmington, California on a troop ship called the Shawnee.