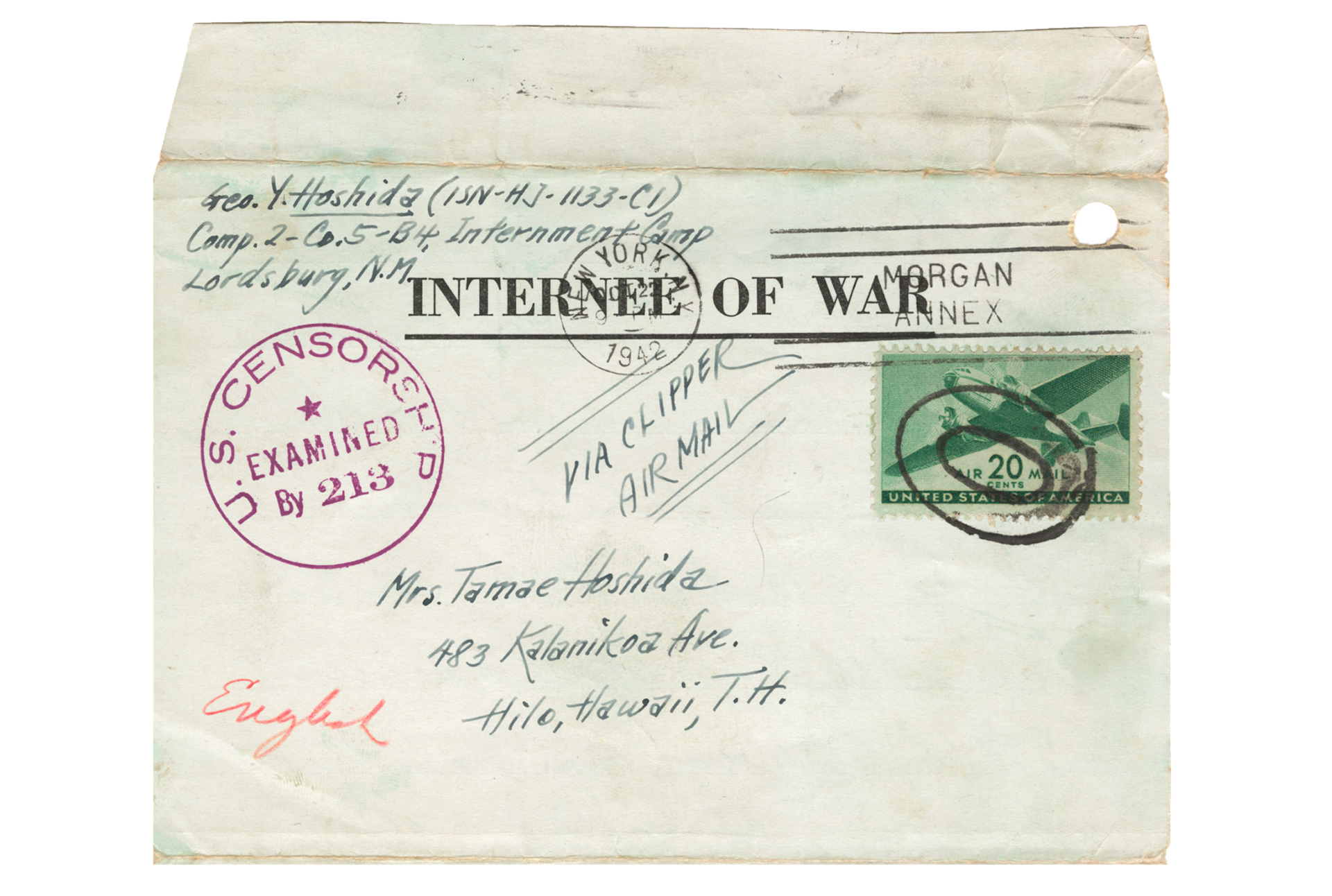

Mr. George Y. Hoshida (ISN-H3-433-C1) Comp.2-Co5-B4, Internment Camp Lordsburg, New Mexico

Oct. 27, 1942

Dearest Husband,

I came home yesterday from the hospital. Please don’t worry because baby and I are doing fine. There’s nothing wrong with the baby. My only regret is that I could not present you with a boy. But even if it’s a girl I guess we have to be satisfied. I’ll be waiting for you to come back and then I guess by then we can have a boy. I’ll be looking forward to that day. By the way you know something she looks a lot like you, her eyes, nose, her lips. She’s all over like you. I only wish you could see her. Of course my friends and relatives come to see me all the time. They treated me very nicely, showering the baby with many gifts. But how I wish I had you here. Even if you were the only one to come and see me, I’d rather have you come than a million others. I never felt so lonely in all my life. Especially when seeing others’ husbands coming to visit their wives. My thoughts are all of you. I guess the baby was lonely too without her Daddy. She would just cry in her little crib. It seems as though she’s calling for you. Oh! how I wish you could see her nose. But I guess that’s impossible so I’ll just imagine that you’re on a long trip that you’re coming back soon so I’ll not feel so lonely. I’ll send you a snapshot of her after about a month later, though I would like to send it to you sooner. But I guess it’s better after I regained my strength so baby and I, in fact all of us would travel together. So please be patient and wait until then. Her name is Carole Aiko Hoshida. I received two of your letters today dated Oct. 4th and 5th. I was very glad to know that you are doing fine and that you are enjoying your stay. Please keep up that spirit and not to worry about home for I am very well taking care of by my relations and friends,...they are very nice to us. I really don’t know how to thank them.

By the way I was very interested in reading your letters. I’m glad to know that you have gained weight. But please don’t get fat like “Baby Elephant” HA! HA! HA! Please write more about what you are doing for both our Grandma’s was very glad to know what you were doing. They all watching for you to come back as soon as war is over. They have been always worried in what you were doing that if you were enjoying yourself, especially what you do to amuse yourself, what recreations. I’ll be waiting for your coming letter, and as for me I’ll write to you as much as possible about how our baby gets along. By the way, I’ve sent you the packages in three the things you requested. I hope you will receive it. Brother, sent the wire through for me about our baby. I hope you get the message. Well, I guess I’ll wait for your letter. Until then take good care of yourself

Your loving wife,

—Tamae Hoshida