Parisian Pursuits: From Wanderer to Salon Success

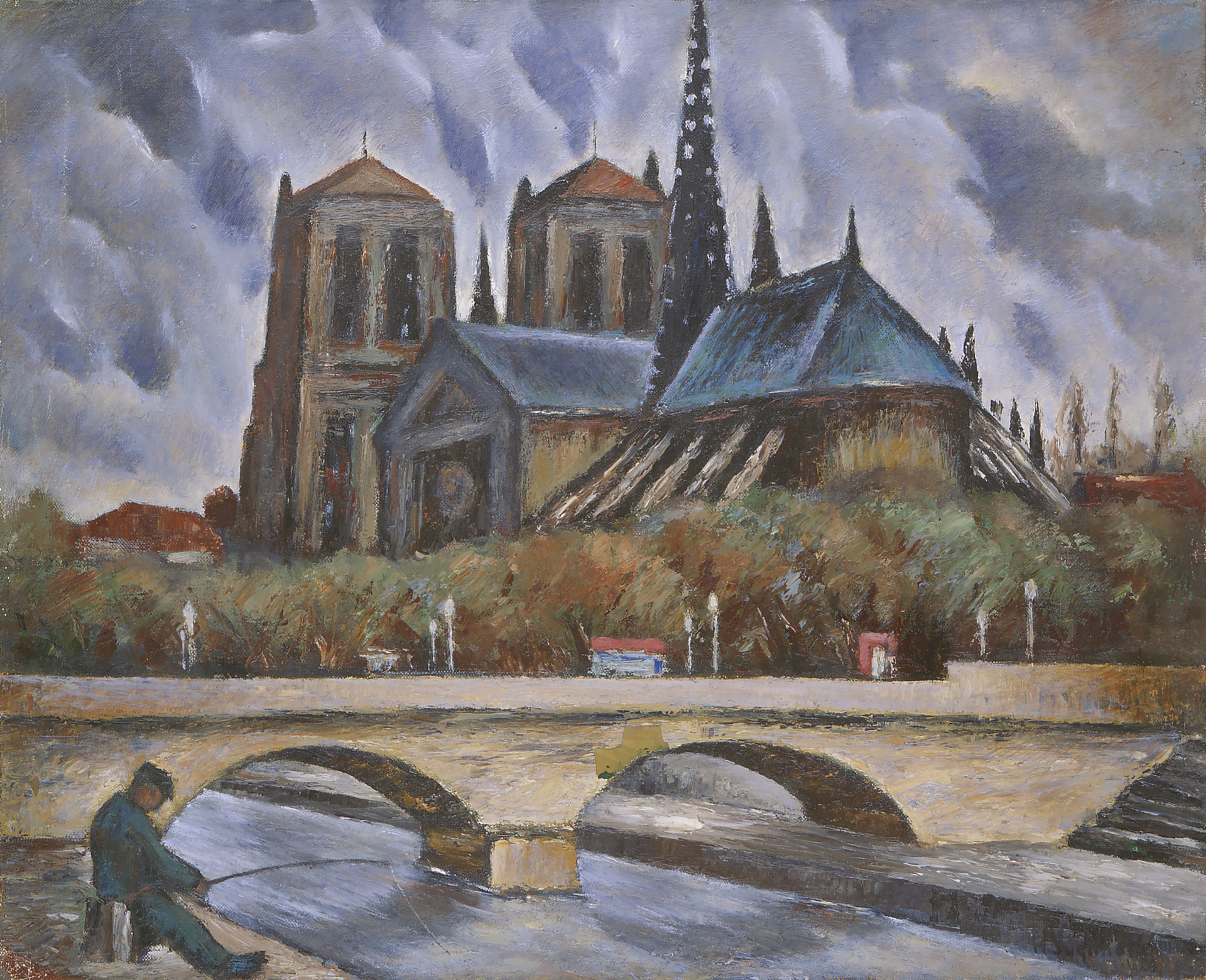

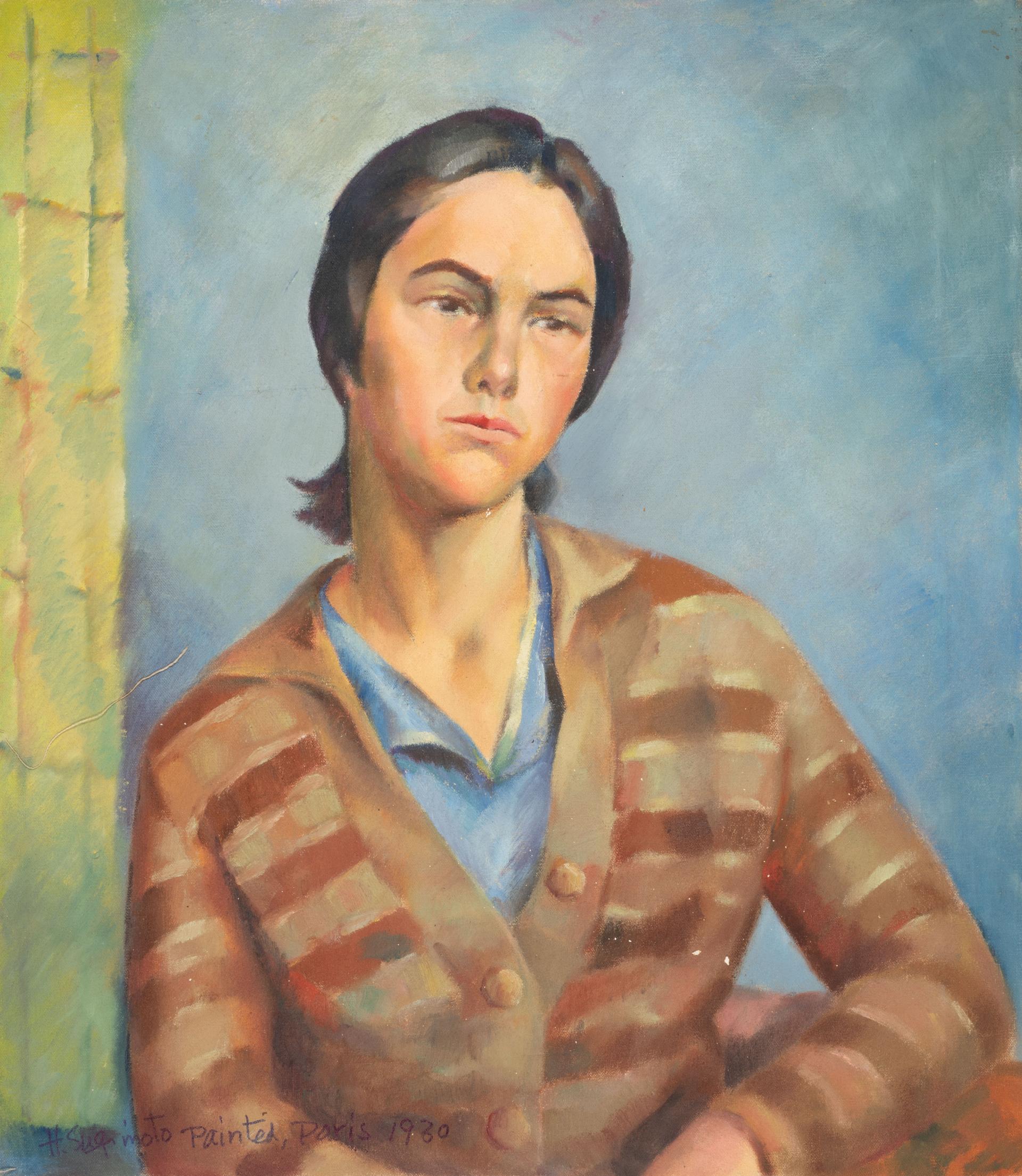

Like many art students during the 1930s, Sugimoto decided to travel to Paris, home to world-renowned artists of Impressionist art. There, he sought the opportunity to see the original paintings of European masters he long admired, including Paul Cézanne and Vincent Van Gogh, and influential contemporary French artists, namely Maurice de Vlaminck and André Dunoyer de Segonzac. In 1930, Sugimoto arrived in Paris knowing no one, so he decided to wander around the city until he met someone Japanese. On his third day, he finally saw someone Japanese in the street, and remarkably, it turned out to be Fujioka Noboru, a painter from New York City.

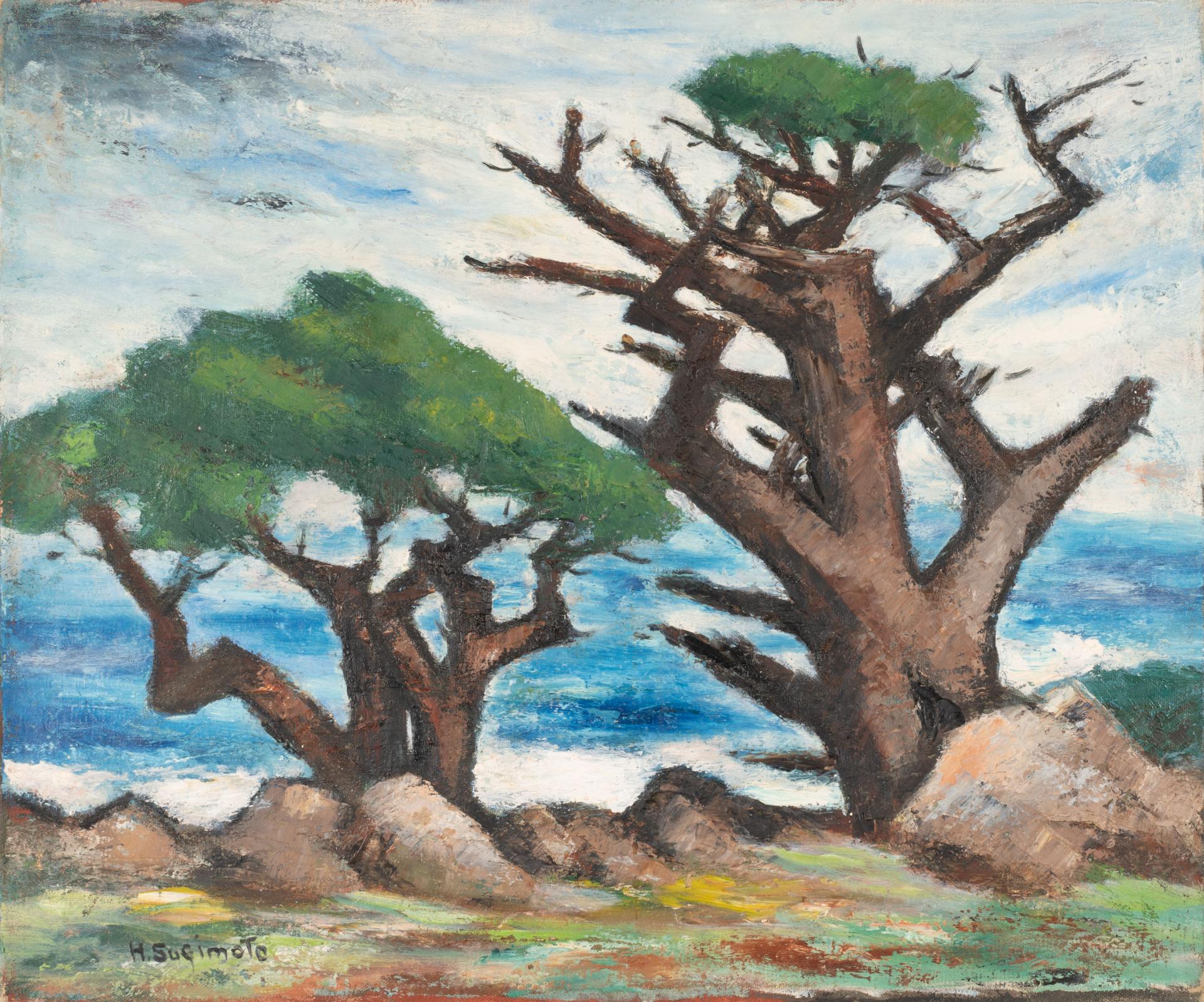

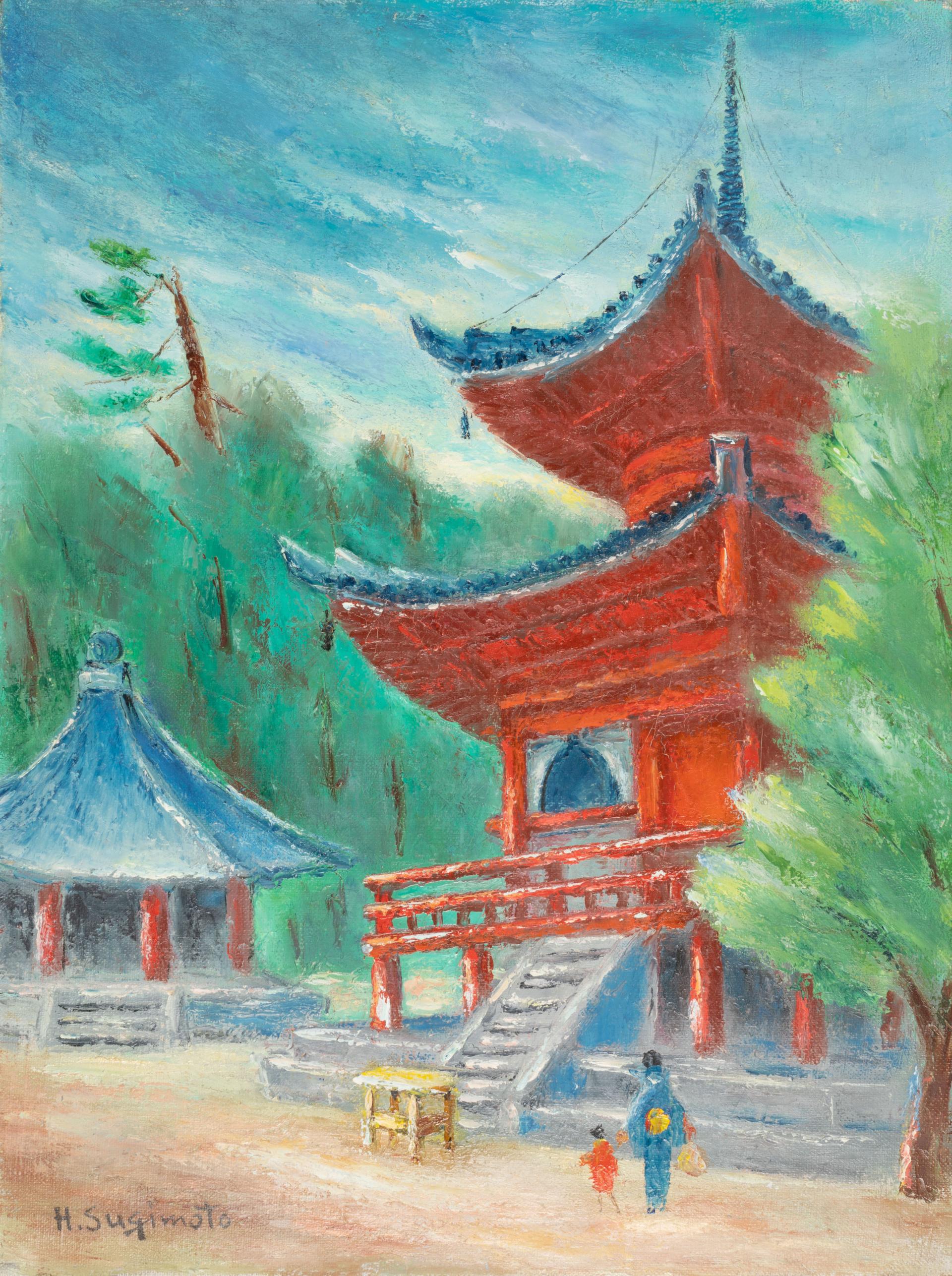

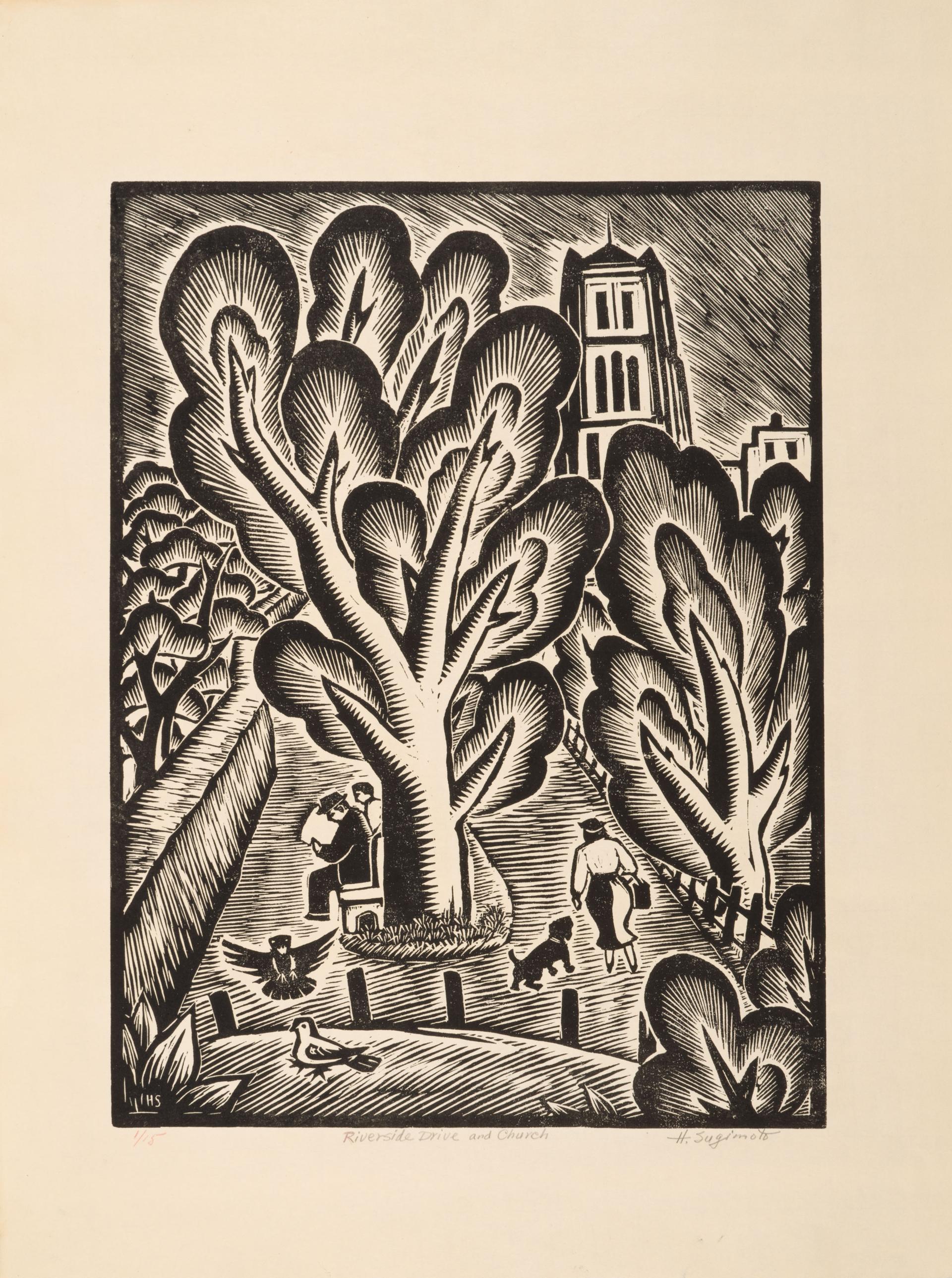

Sugimoto was quickly welcomed in by Noboru and other members of the dynamic community of Japanese artists living in Paris. He proceeded to take French lessons, visit museums, and take art lessons at the Académie Colarossi. One of Sugimoto’s primary goals was to exhibit his work in a Parisian salon, which required success in a competitive selection process. In the fall of 1930, he submitted a painting to the Salon d’Automne, but fell into a depression when his piece was rejected. To remedy his spirits, friends took Sugimoto to the village of Voulangis in the French countryside for a sketching trip. Captivated by the scenery, Sugimoto remained there for the rest of his sojourn in France (apart from short trips). There, he produced a substantive body of impressionist style oil paintings encapsulating landscapes and life in the countryside, honing a rich earth-toned palette and exploring compositions with church buildings, windblown trees, haystacks, and winding paths. The following year, Sugimoto submitted two paintings from Voulangis to the Salon d’Automne, and this time, one entitled Far View of Villiers, was accepted. Soon after this accomplishment, Sugimoto returned to California in 1932 as a matured artist, replenished with confidence and hope for his career.